My only verse from the Talmud I have memorized, and it’s appropriate for Fat Tuesday:

“One day we will be held accountable for all the wonderful things we could have experienced, but did not in this life.”

My only verse from the Talmud I have memorized, and it’s appropriate for Fat Tuesday:

“One day we will be held accountable for all the wonderful things we could have experienced, but did not in this life.”

Today the church remembers and mourns Executive Order 9066.

By executive order of President Roosevelt, Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were United States Citizens, were forced into internment camps on this day, February 19th, in 1942.

It is estimated that, at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, 112,000 of the 127,000 Japanese American residents lived on the West Coast. Of those American residents, around 80,000 of them were second and third generation citizens, never having spent any time in Japan.

Forced from their homes, schools, and places of business, anyone with Japanese heritage (in California they exacted it to 1/16th of Japanese lineage) were placed in regional concentration camps. What was trumpeted as a “security measure” in case any of them were sympathetic to Japan, was actually legalized racism. Such measures were not taken for German or Italian residents in the United States, many more of whom were not legalized citizens (though a small number of people of German and Italian heritage were also forced into these camps on the West Coast).

By this order all people of Japanese heritage were forced to leave Alaska, as well as many areas of California, Oregon, Arizona, and Washington State.

In 1944 a legal challenge to 9066 came to a close, and though its constitutionality was upheld on technicalities (another instance where the small print delayed justice, and it didn’t even opine on the concentration camps themselves), it was affirmed by the court that “loyal citizens cannot be detained.”

The day before the results of this legal ruling would be made public, 9066 was rescinded, an implicit admission of purposeful wrongdoing in my book.

In 1980 Japanese Americans lobbied forcefully to have Executive Order 9066 investigated. President Carter initiated the investigation and in 1983 the commission reported that little evidence of disloyalty was found in the Japanese-American community of the day, and that the internment process was blatant racism. In 1988 President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and officially apologized on behalf of the United States government, authorizing monetary settlements for everyone still alive who had been held in a camp.

In other words: the US government gave reparations. It’s not unprecedented…

The larger question for me, though, is: where was the church?

Why wasn’t the church lobbying hard to have these fellow sisters and brothers released?

Additional studies have shown that religious prejudice also played a part in the justification for these internment camps. In a largely “Christian America,” these often Buddhist, Taoist, and Shinto practicing Japanese residents were seen with much more suspicion (which is probably why the German and Italian residents, also largely thought to be “Christian,” were not rounded up).

The church failed to protect a vulnerable population. The church held hands with the politics of the day in ignoring at best, and aiding at worst, the abuse of other humans.

Today we remember, mourn, and are honest about this failure.

This commemoration is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that when religion holds hands with politics we end up on the wrong side of history.

-historical bits gleaned from Clairborne and Wilson-Hartgrove’s Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals as well as common source news

-for more information on how religion played a part in this stretch of history, visit: https://religionandpolitics.org/2019/07/23/first-they-came-for-the-buddhists-faith-citizenship-and-the-internment-camps/

-art by Norman Takeuchi with his piece, “Interior Revisited,” stated that “Interior and ‘internment’ are synonymous for many of Japanese-American lineage,” because they moved people from the coast to “the interior” of the United States for these camps.

All (the church in Jerusalem) asked is that we (missionaries to the Gentiles) should continue to remember the poor, the very thing that I was eager to do. -Galatians 2:10

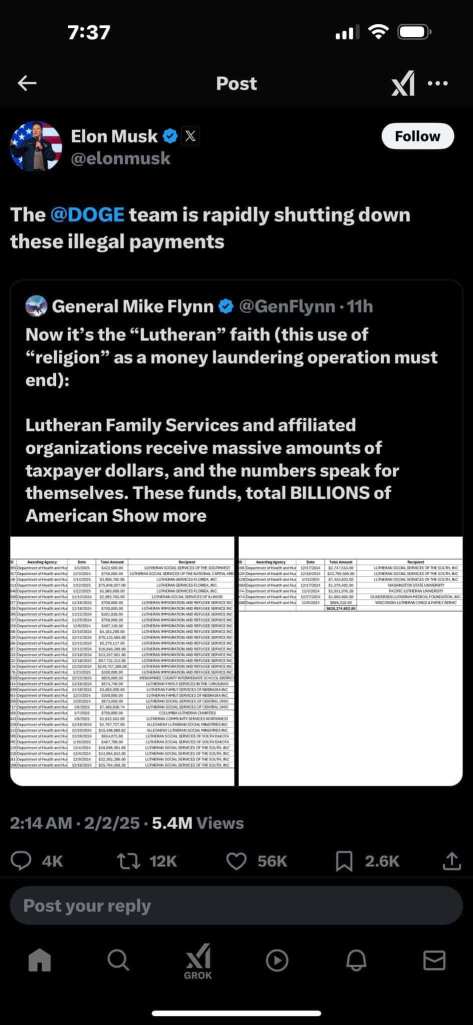

“Any word from the LC-MS (Lutheran Church-Missori Synod)?” a colleague asked me in the hours following Michael Flynn’s disparaging and libelous posting about Lutheran Social Services, Global Refuge and Lutheran Family Services.

A post then affirmed and doubled-down on by the supreme ruler of Department of Government Efficiency (a government “department” in the same way that a “closet” is a “room”…in other words, not really the same thing) Elon Musk.

The post called Lutheran Social Services, Global Refuge, and Lutheran Family Services money laundering organizations.

Which, is not only lauaghably false, but dangerously libel. Especially because on the other end of those services are families in need, children in need, babies, Beloved.

Babies.

And the reason that LSS and LFS have some government contracts (some, mind you), is because they have boots on the ground in localities that need the services and <gasp> do them better than a large beauracratic engine like a government agency could.

I mean, I guess I would put it this way: why use a fire hose to provide a drink when a thousand cups of water will do it better and toward better ends?

That’s what we’re talking about here, Beloved. We’re talking about efficiency and actual impact in actual lives.

But instead of noting that reality, these sledgehammering billionairs and synchophantic parasites decide to prey on misinformation and slander to disparage organizations actually doing the good work necessary for human thriving in the world.

The Presiding Bishop of the ELCA, the Reverend Elizabeth Eaton, was quick to respond. Within hours. As were a number of other Synodical Bishops.

But even though Lutheran Social Services and Lutheran Family Services are pan-Lutheran, and even though Global Refuge has (at least historically) worked across Lutheran denominations, there wasn’t a peep from the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod.

Until there was. Almost a week later.

And it’s no wonder it took a week because what came from the President of the Missouri Synod was, well, weak.

And confusing.

And insulting.

And astonishingly vaccuous.

I won’t bother to read to you the tome (Harrison is in need of an editor), nor will I pick out any of the parts that were particularly troubling (pay attention to his personal opinion on Musk <spoiler alert: praise>). Honestly, slogging through non-speak and word soup once is enough for any ocular exercise…no need to do it twice. No souls will be saved from purgation by going through that torture again.

But I do want to say, quite plainly, why his letter is so disappointing.

I went to Valparaiso University in Valparaiso, Indiana. Valparaiso is a pan-Lutheran university. Quite proudly (or, at least it used to be a point of pride). In our theology department there we had students from both the ELCA and LC-MS learning together.

Debating together. Usually quite collegially.

Communing together (gasp).

Serving together.

Being in honest dialogue together.

And in that ecosystem we embodied the very first church, despite our theological differences.

Because when Saint Peter and Saint Paul disagreed on how to handle ministry to the Gentiles (Paul was for it, Peter was not so sure), they said that, even though they disagreed on a lot of theology, the one thing they could agree on is ministering to the poor (see Galatians 2:10 above).

And I guess that’s why President Harrison’s letter stunk so much.

Stung so much.

Instead of seeing an opportunity to lift up the good work that these organizations do for the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed, he decided to talk about the benefit the church has had in immigrating white folks…but those days are now gone and so, while he empathizes with immigrants, the LC-MS isn’t a part of the work of these organizations.

Because, you know, they help lots of marginalized people. Like gay ones. And “illegal” ones. And they can’t be a part of that even though <checks scriptural notes> Jesus didn’t put any qualifiers on helping the poor and marginalized.

Oh, and he went to the trouble to even note how Flynn probably “meant well” by his “muckraking” which, last I checked, NEVER MEANS WELL.

It’s a kowtow to the powers, instead of speaking truth to them.

It’s the bullied cozying up to the bully so they don’t get picked on.

And it’s sad.

And for those of us who saw how Lutherans could work across ideological differences and even love each other, well…it makes me sad we thought it could be different.

Because the church used to agree on at least one thing: helping the poor.

That was the least it could do for the least of these.

But now?

Not even that can unite us, by God.

And that sucks, President Harrison.

Do better.

“never

trust anyone

who says

they do not see color.

this means

to them

you are invisible.”

-is, by Nayyirah Waheed

We were in the middle of Bible study. Race came up.

She raised her hand.

“I was at a birthday party,” she said, “where I was the only white person. My friend came up to me and said, ‘I guess now you know how it feels a bit, being the minority.’

She went on, “I told her, ‘I don’t see people of color, I just see people.'”

She sat back and smiled.

“It is a sign of privilege,” I said, “to claim not to see color.” That’s all I said, trying to tread lightly. We moved on.

She stopped coming altogether: to the church, the Bible study, all of it.

I sometimes wonder if that’s just what happens when you expose the myth of “non-racist” and invite people to be “anti-racist.” They’d rather just stop showing up instead of doing the hard work.

When we think we’re non-racist is when the hidden biases, the shadow-side of our privilege, are most insidious.

The Triduum, or Great Three Days, is the antidote to an overly saccharine Easter.

Maundy Thursday gathers the disciples, including you, around a shared table where we all get our feet washed and we all share in dipping our bread in the same bowl as Jesus.

Then the sanctuary is stripped, like our souls now feel stripped, as we realize not only what is about to happen, but also that we must stay to bear witness.

On Good Friday we come not to church, but, with everything bare and the lights low, to a darkened tomb. There we encounter the story of that fateful night, a story we know well not only because we’ve heard it every year, but also because we’ve lived it. It’s familiar.

We’ve all been betrayed by our friends, and have all betrayed a friend. We’ve all been falsely accused and accused others without evidence, let alone our unspoken shame knowing our justice system does this, and profits from it all the time.

We’ve all seen power prey on the powerless. This is that story, but instead of the local courtroom it’s the courtroom of the cosmos.

The reproaches are sung where we’re challenged to answer unanswerable questions of eternal proportions, and the service ends with the cross alone left in the room.

We are, in the end, left only with the cross: this twisted tool of torture to which we now cling, hoping that something good can yet come from it.

Sound familiar?

And then we spend the whole next day in the quiet of non-answers. And at dusk we stream back to that tomb, create a new fire to keep our souls warm, and tell campfire stories of salvation to console ourselves.

“Remember that time that God created the world?” we ask around the fire. “And remember when God saved those folks from the fiery furnace?” We retell these stories as a way to spark hope that, as in those impossible moments, God might be able to do something new with this impossible moment. We teach these stories to our babies, even as we reteach it to ourselves.

And then before we know it, the tomb has turned into a lush garden, and that tomb that was full of death is suddenly full of life: flowers, water, and yes, living bodies.

Our bodies.

Our bodies who now gather around the body of the risen Christ now seen in bread, wine, water, and the faces around us. And we baptize people who have newly heard all of this. And we sing and dance and party because, yup, resurrection has happened again, by God!

The whole arc has import. Every scene plays a part.

Easter is not a day, it’s a journey, and now on the far side of that journey, we laugh and dance with memory in one hand and the future in the other.

Happy Easter!

A thought for Holy Saturday:

The night before Easter, after a day of stone-cold silence from God, the people will gather together to build a fire and tell stories around it.

Salvation stories.

Stories like, “Remember when we were saved that one time in the lion’s den, when we were sure we were dead?”

And, “Recall the flood, when we thought it’d last forever, but it didn’t?”

Like tales around a campfire, they’ll tell story after story into the wee hours reminding themselves, and God, about ancient promises until the ground beneath them bleeds resurrection.

Because stories hold power and no tomb can kill Divine promises.

Good Friday thought:

“I’m going away, where you can’t look for me;

Where I go, you cannot come.

And no one’s ever gonna take my life from me.

I lay it down,

A ghost is born.”

-Wilco-

Good Friday thought:

From the cross, the Christ yells, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In this he was quoting the Psalms, his childhood prayer book.

At the end he was doing what he was taught to do as a boy: say his prayers.

A thought for Maundy Thursday:

It might be important for us to keep in mind, especially those (like me) with a propensity to hold on to the slights and wrongs others have done toward us and those we love, that Jesus didn’t skip over Judas when he was washing feet.

Failing to recall this has sometimes perpetuated the pain cycle.

And recalling this has saved me from hurting those who’ve hurt me more than a few times.

-painting by Sister Rebecca Shinas

“You thumbed grit into my furrowed brow,

marking me with the sign of mortality,

the dust of last year’s palms.

The cross you traced

seared, smudged skin,

and I recalled other ashes

etched

into my heart

by those who loved too little

or not at all.”

-Elizabeth-Anne Vanek