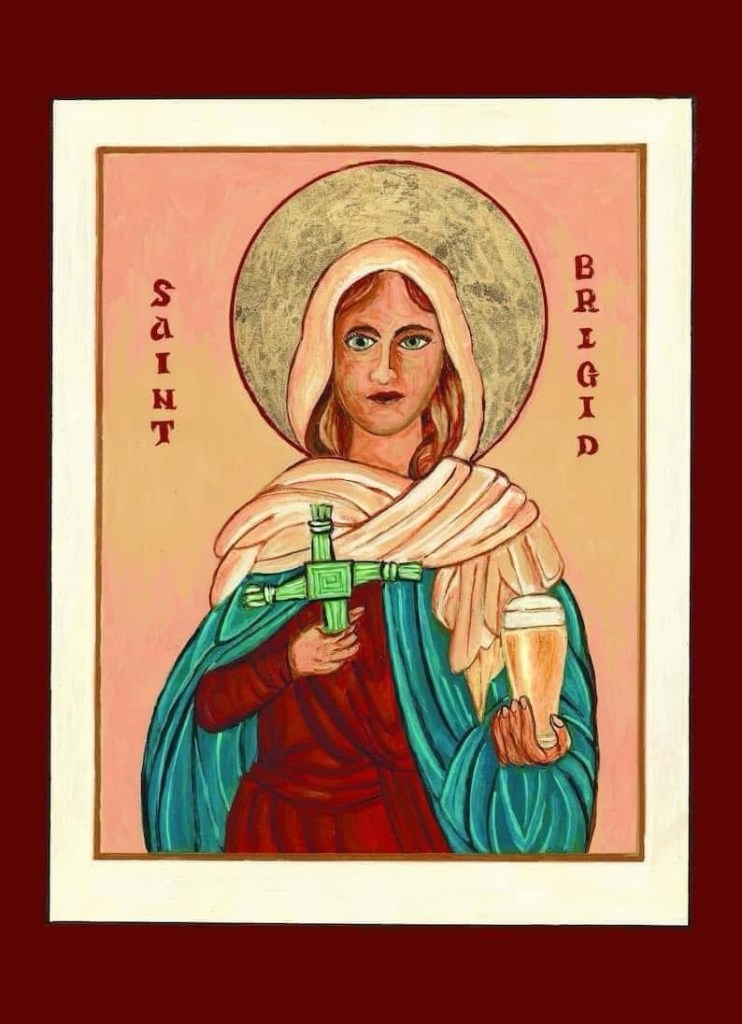

Today the church remembers a Celtic Saint (which makes her close to my heart): Saint Brigid (commonly called St.Bride in Scotland), Abbess and Protector of Ireland.

Sometimes called “the Mary of the Gael,” not much historically verifiable is known about St. Brigid’s early life, though legend and lore abound. On the island of Ireland she is revered as much as St. Patrick in most places, and her story is a mix of Christian and pre-Christian wonder. The daughter of a druid who had a vision from the Divine that his offspring would protect and change Ireland, St. Brigid was said to have been born at sunrise while her mother was walking over a threshold (a point of significance for the ancient Celts, because it meant that she was neither “in nor out” when St. Brigid arrived).

St. Brigid would live into this “neither here nor there” nature throughout her life. She was a peace-loving monastic, but also a fierce warrior. She was both wise and approachable. She was both Christian and pagan in her outlook.

She was known as a strong, happy, and compassionate woman who started a community of women at Kildare in the late 5th-early 6th Century. St. Brigid was said to be wise, and was sought out in life by many for counsel, and admired in death by poets, story-tellers and song-writers who used her as inspiration, many quite fanciful.

Lore has it that it was St. Brigid who spread out her green mantle over all of Ireland to make shine like an emerald.

In Ireland today more than a few rivers bear her name.

In addition to being a wise spiritual leader and community builder, St. Brigid was said to have been the protector of the land, officially the guardian of the pagan king Torc Triath of what is now West Tipperary. In a time when Ireland was a destination for all seafaring people, the need for protection was great. St. Brigid was an accomplished warrior. In ancient Celtic culture women were seen not only as capable leaders, but in many areas superior.

St. Brigid died in the early 6th Century, and her following grew to the point that her relics were prized possessions that had to be continually moved and hidden from invading marauders who sought to steal them as a trophy.

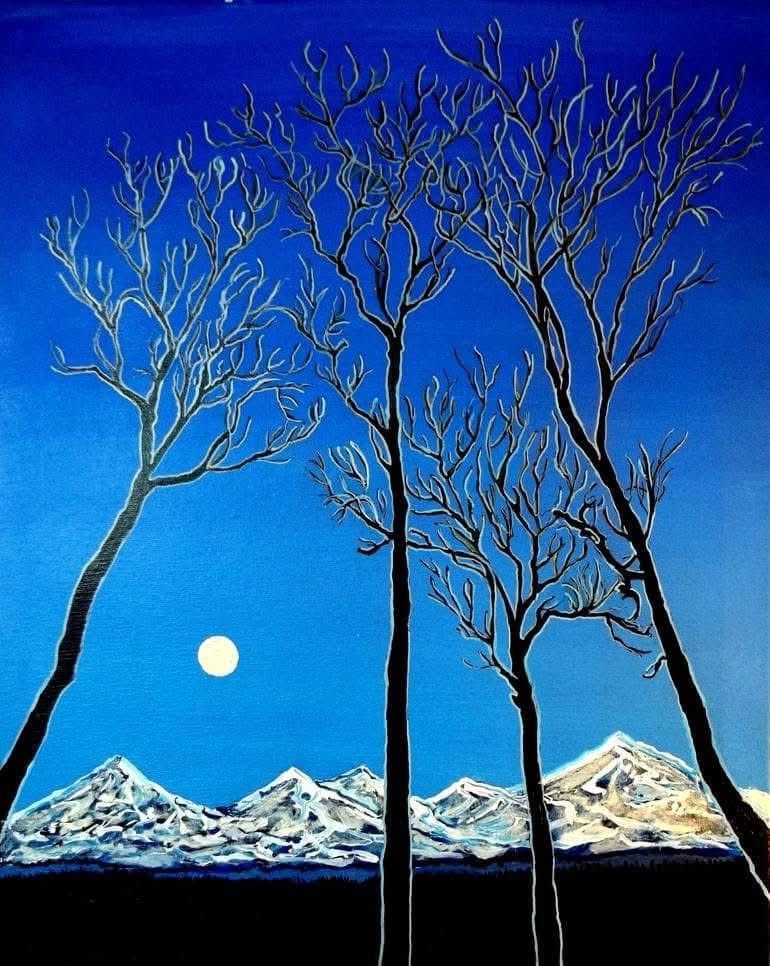

The most remarkable thing about St. Brigid, though, is not her historical self, but the part she now plays in Celtic Christianity. St. Brigid’s day comes in the “dead months” (marbh mhios) of winter when humanity in the northern hemisphere finds itself “Imbolc” or “in the belly” of winter. Her feast day is a reminder for the Celtic Christians that winter doesn’t last forever, and though you now might see only shadows, the sun is growing stronger every day, by God.

This reminder of St. Brigid, woman of wisdom and strength, works for the winter of the seasons, and in all the metaphorical winters of your life, Beloved.

St. Brigid is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, at least three things:

First: live in such a way that people write wonderful stories about your wisdom and strength.

Secondly: the intermingling of Christian and non-Christian sensibilities has helped the faith to develop, and this can be seen in no better place than in Celtic Christianity.

Finally: though we must live with winter, it never lasts forever.

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

-historical bits gleaned from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals and Commemorations

-Celtic lore found from stories of my ancestors as well as Freeman’s Kindling the Celtic Spirit

-icon written by Larry at IconWriterArtist on Etsy