Did some writing for a magazine called Living Lutheran this past month.

Feel free to take a gander…

Did some writing for a magazine called Living Lutheran this past month.

Feel free to take a gander…

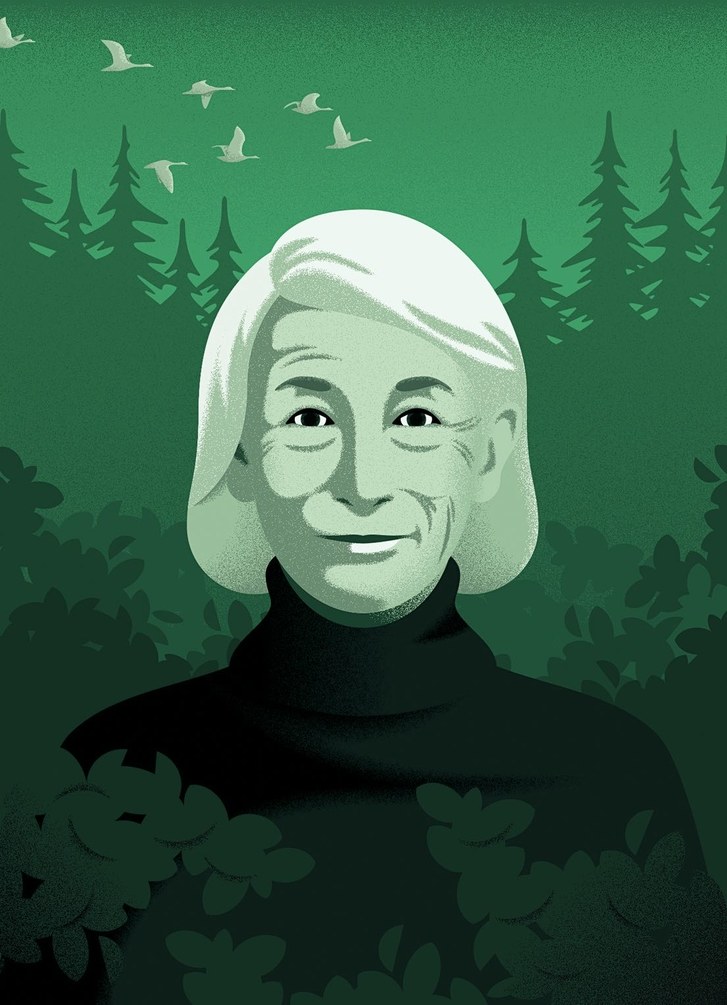

I don’t remember when I first read her work. I’m sure it was in my twenties.

I don’t remember when I first read her work. I’m sure it was in my twenties.

Because in my twenties I knew too much. Everything, actually. And if you doubt that, just ask my 27 year old self. I would smile demurely and shy away from your question, but secretly answer in the affirmative.

And then enter Mary.

Mary, the poet.

Mary, the theologian…though unwittingly, perhaps.

Mary, with her short stacked sentences packed on top of one another like pancakes, dripping with meaning.

Heavy, sweet meaning.

Her observations on simple things, like ducks and pipefish, made me wish I knew how to engage with the world in a way that still retained the wonder and awe and love of my young self.

And she was doing it in this way until she was quite old!

She helped me to realize that I knew not only nothing about things like ducks or pipefish, but I knew nothing about a life observed and that I better get with the program, better surround myself with poetry, if I was ever going to know anything about anything.

Let alone, myself. My life.

Poetry helps us to observe life, and observe it intently. With feeling. With hope and a good bit of angst and…good grief.

It is something, when it works.

Poetry is the picture that prose wishes it could paint.

Poetry is the picture, mind you. It doesn’t paint it; it is it.

Poetry is prayer both for those who are sure “prayer is perfectly fine for other people” and for those for whom prayer is every breath. It unites the faithful and the faithless in fancy couplets where they’re forced to hold hands, at least for a moment.

It is subversive.

Submersive, if that is a word. It doesn’t matter…that’s what it is.

It is like water, winding its way through your soul as your eyes are jarred by

unexplained breaks

and

dangling groups of letters that

just make you hold on because you’re never sure when you’re going to

jump.

…

And when you do jump, when you build up the courage to actually engage poetry like an explorer spelunking into the cave of words, you crash into meaning.

And your heart breaks.

Like mine did when I first pondered what I’d do with my “one wild and precious life.”

And you’re never put back together in the same way again, thank God.

Her collection House of Light sits on my desk. I crack it for inspiration quite a bit.

But my favorite of her poems is this one below. And it’s the one that I’ll end with, I think, because, well, she’s finally made the journey.

And let me tell you: with her wild and precious life she broke my heart.

And I am grateful for it.

The Journey

I first read Timothy Keller’s book, The Reason for God, after reading an article on him in Newsweek. I was intrigued by his approach to ministry and his interactive preaching style. Although his theology is a bit more conservative than my own, I think he’s quite a good scholar, and quite good at message conveyance.

The Reason for God did not disappoint in either its scholarship or its clarity. Keller’s impetus is to provide for the reader his reasoning for belief in a God, specifically the God known through Christ, and you get an adequate picture of both what his belief is and the pillars that sustain his logic. And I have to say that I found myself nodding more than shaking my head.

The book is configured into two primary sections: “The Leap of Doubt” and “The Reasons For Faith.” Both are intertwined with narrative and questions that Keller has received over his years of ministry at Redeemer Presbyterian Church (PCA), with Keller providing responses and answers.

Actually, I would call them “pseudo-answers,” because, while they appear to answer the question, Keller writes with an overconfidence and overstatement that I just can’t fully stomach.

In Keller’s attempt to wrap things up tightly for the reader (and convert the reader, I suspect), he leaves large gaping holes that go unacknowledged. You don’t need to read far in the work to fall into one. Chapter 2, “How Could a Good God Allow Suffering,” is one such example. Although I think Keller is on the edge of some really wonderful thinking on the issue of systemic suffering (his section entitled “Evil and Suffering May Be [If Anything] Evidence for God” deserves a second and third look…despite the appalling title), he ends spouting the same old argument heard before and wished for by anyone who has ever suffered: that the past suffering makes the future joy that much better.

I don’t think that’s true. And even if it were, I don’t think it’d be helpful to say. Ever.

Chapter 7, “You Can’t Take the Bible Literally” is another example of taking an argument too far, and represents, I think, the lowest point in the book for me personally. Although he makes some perfectly good arguments, he often ruins them with ridiculous rhetoric. One example can be found on page 105:

Mark, for example, says that the man who helped Jesus carry his cross to Calvary ‘was the father of Alexander and Rufus’ (Mark 15:21). There is no reason for the author to include such names unless the readers know or could have access to them. Mark is saying, ‘Alexander and Rufus vouch for the truth of what I am telling you, if you want to ask them.’ Paul also appeals to readers to check with living eyewitnesses if they want to establish the truth of what he is saying about the events of Jesus’ life (1 Corinthians 15:1-6). Paul refers to a body of five hundred eyewitnesses who saw the risen Christ at once. You can’t write that in a document designed for public reading unless there really were surviving witnesses whose testimony agreed and who could confirm what the author said. All this decisively refutes the idea that the gospels were anonymous, collective, evolving oral traditions…

Really? Decisively? Keller drops the ball here in scholarship, and going against the overwhelming view of modern theologian/historians, claims too much. While it does seem that the author of Mark (conveniently often called “Mark”) is name dropping for a particular reason, we can only speculate why. Perhaps it was because Rufus and Alexander were still around. Or could their insertion be an interpolation? And I completely disagree with his idea that Paul’s letters were meant for public proclamation. I think it is reasonable to believe that Paul expected his Corinthian letter(s) to be read to that church, but can we really claim that to be “public” or that the church that received them would scrutinize them? To me that sounds like a Western mind (Keller’s) trying to put its own lens on Eastern thinking (Paul and the church at Corinth’s).

I found his strongest thinking in Chapter 9 where he addresses morality and the knowledge of God. In looking at a number of conventional arguments on the subject, Keller provides a very accessible description of the popular thinking of how morality is found, configured, and reinforced in this world, citing both Annie Dillard and Ronald Dworkin in his formulation. Yet again, he goes too far in answering the question for the reader, instead of just letting the question hang (as, I think, all theological questions should).

This book is worth the read if you can take the over-confidence. Keller presents wonderful arguments. But, like with all things, one shouldn’t be totally persuaded. Over-confidence in one’s own arguments can lead to idol worship, and Keller’s conviction of his correct beliefs borders on that.

But, then again, I really have yet to find an author on this subject that isn’t over-confident. Including the author of this blog.

I love it when people use the phrase, “elephant in the room” to describe that taboo topic that needs addressing in public. Everytime I hear it I visualize that elephant and just where she might be standing. I usually imagine her in the middle eating peanuts.

I love it when people use the phrase, “elephant in the room” to describe that taboo topic that needs addressing in public. Everytime I hear it I visualize that elephant and just where she might be standing. I usually imagine her in the middle eating peanuts.

Here’s an elephant in the religious room: there are Biblical inconsistencies.

Not an elephant for you? Not for me either. But it is for some people, apparently. Or at least, was.

Take Bart Ehrman, Professor of Religious Studies at UNC, Chapel Hill (go Tarheels!) for example. He was trained in a conservative tradition where the Bible is viewed as inerrant. Going from Moody to Wheaton to Princeton, that view evolved much to his sadness, and he’s written about it.

A lot.

Misquoting Jesus, God’s Problem, Jesus, Interrupted, these are all books which pull back the curtain, as it were, on what he believes people think or have thought about all things Christian, from the words of Jesus to the compilation, contents, and meaning of Scripture.

I was introduced to Jesus, Interrupted by a congregation member. He was reading it, so I figured I should read it.

I found it to be well written, but not particularly instructive. The congregant, on the other hand, found it to be totally disruptive. In short: it was faith-shattering.

Ehrman, too, lost faith after studying at Princeton and finding out much of what he has recorded in Jesus, Interrupted. Apparently finding out that Moses didn’t write the first five books of the Old Testament (surprise surprise, especially considering that if the historical Moses were based off of a real individual he was probably illiterate…and would probably not write in meta-Moses form about his own death) was faith destroying. Or if not that, perhaps it was learning that the end of the Gospel of Mark was added at a later date because it was just too much to have the “women say nothing to anyone” after the resurrection. Or perhaps finding out that in the Gospel of John Jesus dies on a Thursday, whereas the synoptics have him dying on a Friday.

Perhaps it was all of these that caused Ehrman to lose faith; perhaps something else.

My point, though, is that I learned all of this at university, and was taught much of this in seminary.

And here I am, a Christian (reluctantly).

And learning it didn’t destroy my faith at all, it just reconfigured it.

I lost faith in the words, but grew in faith to the story the words pointed to. I lost faith in the empirical thinking that we for some reason believe must rule our lives, and fostered faith in the storied thinking that truly moves mountains and inspires action.

Dr. Ehrman: in what was your faith? Was it in the words, or was it in the promise the words pointed to?

In seminary I had a classmate who said boldly, “Even if tomorrow they find the bones of Jesus of Nazareth, I still hold fast to the promise…that is the nature of faith.”

Indeed, it is.

Religion does no good in espousing the inerrancy of its documents, creeds, doctrines, dogmas…whatever. I have no doubt that people are leaving churches in flocks because they find that their faith in the inerrancy of Scripture cannot stand up to the fact that Paul probably did not write all the letters ascribed to him.

I should also mention that, the early church probably knew this and it didn’t seem to challenge their faith any…

But I do empathize with faith-destruction. It’s tough. Even Christopher Hitchens has a touching moment in God is Not Great where he speaks of his disollusionment with Marxism, and likens this to the religious individual losing faith. He writes,

“Thus, dear reader, if you have come this far and found your own faith undermined-as I hope-I am willing to say that to some extent I know what you are going through. There are days when I miss my old convictions as if they were an amputated limb. But in general I feel better, and no less radical, and you will feel better too, I guarantee, once you leave hold of the doctrinaire and allow your chainless mind to do its own thinking.” (God is Not Great, 153)

The rub? Hitchens and Ehrman point to the same evidence in both of these books. Sure, Ehrman is less flippant and less inflammatory, but the gist of their arguments are the same.

And their purpose, I think, is probably the same.

And where is the defense of faith? Usually found in the voice-box of a literalist…and thus the elephant enters back into the room. Spong and Borg are attempting, Craig and McGrath are making some good noise, but the fact of the matter is this: if we are to defend faith as a life-giving concept, we have to stop teaching ridiculous notions like Biblical inerrancy, which are nothing but death knells waiting to ring.

Where is the emphasis on stories and how story shapes our reality? Where is the emphasis on promise, beauty, love that defies description?

I read Hitchens and Ehrman, and find myself nodding a lot. A lot of what the atheist and agnostic says makes sense to me, a reluctant Christian. But none of it destroys my faith. So either I’m deceiving myself (the Truth is not in me, I assure you), or my faith is in something other than words on a page or empirical proof.

So now, what are we to do?

Perhaps we can start by ushering the elephant out of the room, and then tell a story. That’s what this a/theist does.

Lennie and George speak in broken conversation. George telling, and retelling Lennie about the farm that they’ll have one day. Lennie basking in the glow of this beautiful thought: rabbits of his very own.

Lennie and George speak in broken conversation. George telling, and retelling Lennie about the farm that they’ll have one day. Lennie basking in the glow of this beautiful thought: rabbits of his very own.

But George cautions Lennie when it comes to cats. Afterall, every farm has to have cats to keep rodents away…and to generally complete the requisite animal quotiant to relegate a dwelling a “farm.”

“We’d have a setter dog and a couple stripe cats, but you gotta watch out them cats don’t get the rabbits.”

And Lennie really only desires the rabbits.

“Lennie breathed hard. ‘You jus’ let ’em try to get the rabbits. I’ll break their God damn necks. I’ll….I’ll smash ’em with a stick.’ He subsided, grumbling to himself, threatening the future cats which might dare disturb the future rabbits.”

Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men is a great study in literature…and a great study in people. Lennie’s defense of that which he desires most, rabbits (or the feel of rabbit fur, or the idea of keeping fur around without breaking the necks of the furry, or whatever you deem his deepest desire is), is typical of people, I think. In fact, I would say that this reactionary defense is probably the one lone characteristic in Lennie that is not affected by his cognitive struggles.

We defend most heartily that which we desire most.

I received a communication recently from a good friend and fellow pastor asking about the apparent dichotomy created in my first post between doctrine and dogma on the one hand and the Jesus movement on the other. This friend was quick to point out that he wasn’t disagreeing, but simply wanted some clarification:

Didn’t the Jesus movement necessarily need doctrine (and the creation thereof) in the face of Donatism, Docetism, Arianism, and other such challenges?

The short answer: yes. Of course. In any sort of conception of a theological position there is never an “a-position.” That is, even if you claim to stand nowhere…that is a stance, a place, a position. The Jesus movement surely needed to refine, re-think, re-discover it’s position on the role of pastors, on the person of Christ, on the oneness and threeness of God…

Yes, of course.

But they are rabbits, are they not? Dreams of a possibility that can’t yet be touched.

They’re not imaginary; they’re very real. But they’re only real in so far as they point to the Real. If they go further, they become no longer the symbols, the subject, of the desired, but the object of desire.

“I desire Trinity.” “I desire Orthodoxy.”

Instead of, “I desire the God that the doctrine of the trinity helps me to wrap my mind around, if incompletely.”

Instead of, “I desire the God that orthodoxy (however defined) wants to show.”

We need a re-traction of doctrine. Doctrine should not give something, but should point to something…point outward, further than itself.

Back to Rollins:

“The job of the church is not to provide an answer-for the answer is not a phrase or doctrine-but rather to help encourage the religious question to arise…the silence that is part of all God-talk is not the silence of banality, indifference or ignorance but one that stands in awe of God. This does not necessitate an absolute ‘silencing,’ whereby we give up speaking of God, but rather involves a recognition that our language concerning the divine remains silent in its speech.”

We say too much in saying anything, and say too little in saying nothing.

But doctrine, for all its benefit, has become a rabbit.

“Believe this and be saved. Attack this and I’ll smash you with a stick.”

This past weekend I watched religious TV on Sunday morning…the bed and breakfast had cable. I flipped through four different religious programs. Some were complete services, some were snippets of “teachings,” some were call-in shows. Very different.

Yet very similar.

They each promised to give the viewer something. One was “The Four Essentials of Faith.” Another was, “How God can Help your Wealth.” Fill in the blank here with some other infraction on the Second Commandment, as I am most certain that God does not want to help you, or me, get wealthy in any sort of way that we would identify as wealth…

And they each reminded me of why I’m a reluctant Christian.

These programs are so popular with their lovely memes impregnating the minds of views, both live audience and electronic audience. And this is the mistaken, idolatrous promise (illusory as it is) of doctrine: it gives you something.

Instead, the real promise of doctrine is that it points to something…points past itself.

Please, Lord, save me from being saved and all the wonky ways we’ve devised to save ourselves from each other, from other doctrines, from, whatever it is we run from.

“The religious individual tears out all the idolatrous ideas that have impregnated the womb of his or her being, becoming like Mary, so that the Christ-event can be conceived within him or her-an event whose transformative power is matched only by its impenetrable mystery.”

Do we need doctrine? In so far as it points us toward that which is beyond our knowing, yes.

Do we need to be saved from doctrine? In so far as it has become our rabbits, mice, soft toys to pen, and hold, and pet, and defend with sticks, yes.