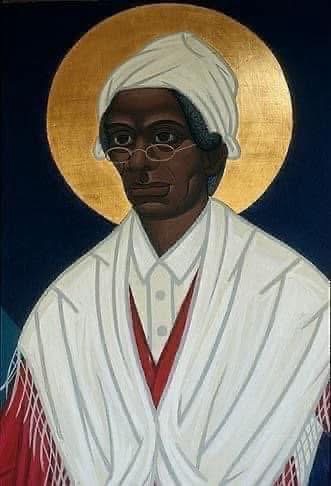

Today, in the middle of Women’s History Month here in the States, I would lobby hard that the church remember a modern day saint who was the first woman to ever appear on United States currency: Saint Susan B. Anthony, Abolitionist, Suffragist and Sufferer of No Fools.

Saint Susan was born in 1820 to working-class Quaker parents in Massachusetts. The Quaker ethos would forever be a golden thread running through Susan’s life as she spent years teaching children, and then eventually met up with two other saints, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, both who were friends with her father.

This meeting forever moved her heart, and she decided to throw her voice behind the abolitionist movement despite the headwinds of patriarchy that told her that women should not speak in public spaces.

In 1851 Susan met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a new adventure began in earnest: the fight for suffragist movement. For over fifty years Susan spoke and advocated and marched for the right for women to vote. She was mocked for it. She was denegrated for it. She was even threatened with arrest at times.

And still she persisted.

Saint Susan, like all saints, was not without her flaws. Through the backward lens of history (as Kierkegaard said, “Life is understood backwards but lived forwards…”) we can see that her opposition to the 14th and 15th Amendments that gave African American men the right to vote was short sighted. Part of their critque was the absence of women from the bill. Part of it was probably due to the ugly factor of deep-seeded prejudice that is wiley and pervasive.

In 1872 Saint Susan was arrested for voting and charged $100. This act of civil disobedience only emboldened her cause, and suffragist movements popped up all over the country, merging together into large forces, marches, and vocal activists that could not be ignored. The National American Women’s Suffragist Association was born as a merger of two of these organized entities, and Saint Susan led them until 1900.

She died on this day in 1906, never fully realizing the goal of her cause…the 19th Amendment would not be ratified until 1920…and yet, it persisted.

Saint Susan B. Anthony is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that sometimes we don’t see the fruit of our labors for justice and equality.

And yet, we must persist.

-historical bits from public sources

-minimalist design by thefilmartist available for purchase at redbubble.com