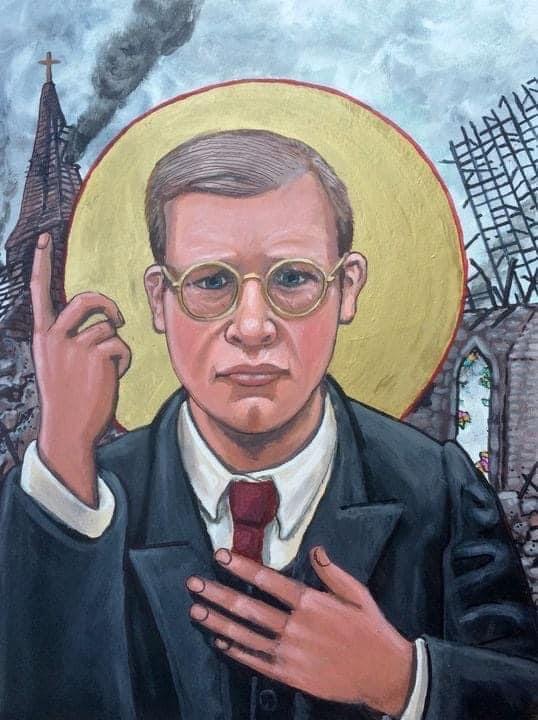

It’s worth noting that today the church remembers a contemporary saint who took wrestling with demons, both in his heart and in his country, seriously: St. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Teacher, Martyr, Gadfly of the Nazis.

Born at the turn of the 20th Century in Breslau, St. Dietrich grew up in the intellectual circles of Germany. He studied hard, was trained as a scholar and theologian, and as a young pastor he moved to both Barcelona (where he was assistant pastor at a German-speaking congregation) and then to New York City where he was a visiting lecturer at Union Seminary.

It was during his time in New York that he felt his guts calling him to return home to Europe, the belly of a waking beast, and fight for the soul of his people from the inside. As the Nazi party ascended in 1933, the growing anti-Semitism was alarming to him as a person of faith. From 1933-1935 he served as the pastor of two small German congregations in London, but became the voice of the Confessing Church, the Protestant resistance to the Nazi party’s coopting of the national church. He made his way back to his homeland with both conviction and trepidation.

In 1935 St. Bonhoeffer organized a new underground seminary to train theologians in the art of subversive resistance (because the Divine is subversive!), and he began publishing the thoughts flowing from his heart in this difficult, hidden work. Life Together and The Cost of Discipleship describe the role a Christian is called to play in times of turmoil, and he encouraged his fellow believers to reject the “cheap grace” that smacked of moral laxity.

In 1939 St. Dietrich was introduced to a cadre of political exiles who sought to overthrow Hitler. Working with other church leaders throughout the world, including the Bishop of Chichester, St. Bonhoeffer tried to broker peace deals, but to no avail. Hitler could not be trusted to keep his word, and so the Allies would only accept unconditional surrender.

Bonhoeffer was arrested on April 5th, 1943, shortly after proposing to the love of his life. An attempt on Hitler’s life had failed the previous year, and documents were discovered linking St. Dietrich to the plot.

After a short stay in the Berlin jail, Bonhoeffer was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp, and then on to Schonberg prison. There he wrote letters to his best friend and his fiance, and conducted pastoral duties for the prisoners there.

On Sunday, April 8th, 1945, just after he concluded church services, two men with weapons emerged from the forest, not unlike the soldiers in the Garden of Gethsemane. They said, “Prisoner Bonhoeffer, come with us!”

Bonhoeffer, putting up no fight, said to his fellow prisoner, “This is the end. For me, the beginning of life.”

He was hanged in Flossenburg prison on April 9, 1945.

St. Bonhoeffer wrestled deeply with evil in the world. He was a pacifist theologian, and yet he involved himself in the plot to destroy Hitler because he felt that to not do so would be a greater evil than the man’s death.

St. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church (everyone?!), that wrestling with evil must be something everyone does with honesty and conviction, and that sometimes it comes at a price that can be quite high.

Grace is free, but not cheap.

-historical bits from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-note that sometimes I use the phrase “saint” in the Protestant definition of the word: someone who has died in the faith. Bonhoeffer is not canonized by any official means, just within the hearts of those of us who trust subversion to be the ways of the Divine

-icon written by Kelly Latimore. You can buy his amazing work at https://kellylatimoreicons.com/