Today the church remembers a prophet-farmer who spoke from the margins for the margins: St. Amos of Judah, Critic of the Monarchy and Firebrand Defender of the Poor.

St. Amos was active between 8th century BC, and is considered one of the twelve minor prophets in the Hebrew Scriptures (Hosea, Joel, Jonah…they round out the rest). The book of Amos is attributed to him, and though he was from the Southern Kingdom (Judah), he preached in the Northern Kingdom (Israel).

Having felt the call of the Divine upon his heart from the rural outskirts of the kingdom (and of society), Amos is a farmer-turned-prophet who pointed the monarchy toward the margins and asked, “Do you see who you are neglecting?! You claim to be working on behalf of God, but the growing wealth and opportunity gap between the elites and the working poor exposes your talk as just lies!”

Seriously, that’s the gist of his argument.

He said, “I am not a prophet, nor the son of a prophet!”(Amos 7:14) are his attempts to get the elites to listen to him. In essence he said, “I’m not doing this for show, y’all! This is real life.”

He warned that not watching out for the welfare of the weakest would lead to the Northern Kingdom’s fall. And, well, the Northern Kingdom fell in time…

As the wealthy continued to amass lands that did not belong to them, and on which they did not work, Amos reminded the circles of power that their goal was to honor God by protecting and elevating the laborer, not to get the “best deal” and take advantage of them.

Justice. Egalitarianism. A preference for the poor and the margins. This was the cry of the prophet Amos.

At his core Amos sought to do something that, throughout history, has been the hardest thing to do: convert the wealthy and the comfortable.

The feast day for this Biblical prophet varies depending on tradition. The Armenian and Orthodox calendars place the day in the summer months (June 15th or July 31st), while the Roman branch waits until March 31st.

Today, though, is an excellent day to honor the firebrand of a saint as March 28th often lands in the season of Lent, a season where we attune our spiritual hearts toward repentance.

St. Amos is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that in times of prosperity conversion is still necessary…and often it has little to do with “giving your heart to Jesus,” but rather offering up your life and gifts for the sake of your neighbor.

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

-historical bits gleaned from publicly accessed information, the Harper Collins Study Bible, and Claiborne and Hartgrove’s Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals

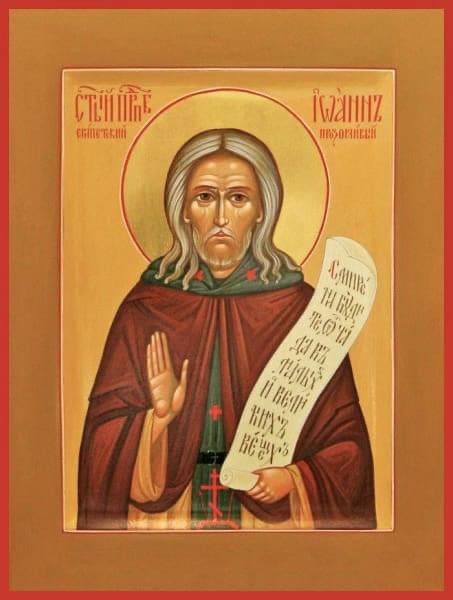

-icon is a Russian Orthodox depiction of the prophet making their appeal.