Today the church unofficially honors one of its moveable commemorations: Good Shepherd Sunday.

The lectionary (prescribed calendar of readings for the church) annually incorporates shepherd imagery into this Sunday of Eastertide, giving a nod to both the agrarian notes of the ancient scriptures as well as an allusion to the Davidic tradition within the canon.

Ironically, of course, this Sunday’s reading from John focuses more on Jesus being a gate than a shepherd, but we won’t go there today.

The image of a shepherd king is a striking one, though it probably doesn’t feel that way to our modern sensibilities. Shepherds were not highly thought of (they couldn’t testify in ancient courts because they were seen as too “woodsy” and “backwater” to tell the truth), and their work was seen as menial labor. Yet it is from this stock that the Divine chose the preeminent king, David. And it is to these people that the angels first came to sing of the birth of the Christ.

It’s ironic that both Christ’s birth and Christ’s resurrection were first proclaimed to people who couldn’t offer official testimony in court (shepherds and women). God chooses the lowly and marginalized to hold Divine promises.

What passes for popular Christianity would do well to remember this as they pass laws in state houses to further marginalize the marginalized and silence voices who they consider ”other.”

Shepherds in the ancient world would rescue sheep, fight off predators, and sometimes carry errant, injured, or wayward sheep on their shoulders, keeping them with the flock (often despite the sheep’s best efforts).

On this Good Shepherd Sunday, though, perhaps it’s more appropriate to remember that in Jesus we see a God who is not “kind and caring” so much as a person on the margins themselves.

Which makes me wonder: if God is embodied in the marginalized, why do we treat folks on the margins of society so badly?

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

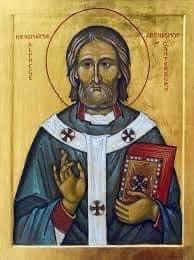

-icon in the Byzantine style