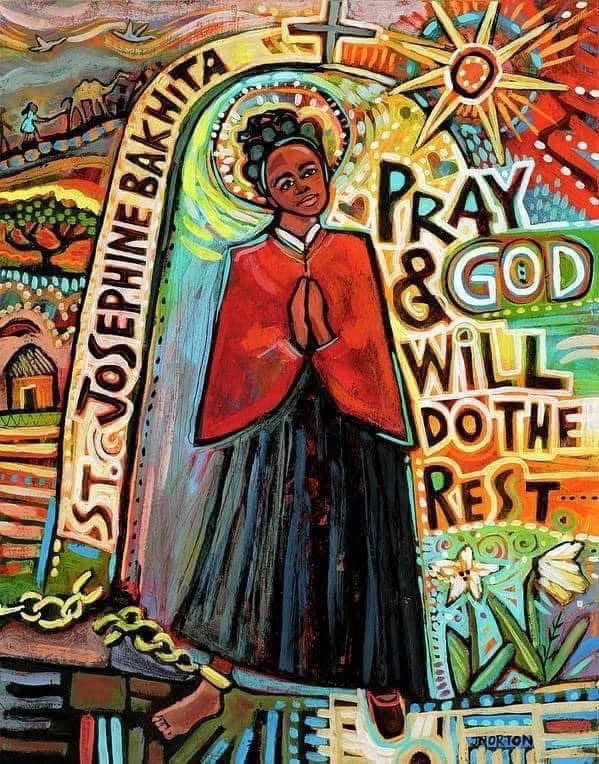

Today the church remembers a 20th Century Sudanese saint remembered for her fierce bravery and gentleness: Saint Josephine Bakhita, Patron Saint of Those Caught in Human Trafficking.

Saint Bakhita (not her given name at birth…the trauma of her story prevented her from remembering her birth name) was raised in Darfur by her loving family until the age of eight. At this young age, she and her sisters were captured and forced into slavery, sold a number of times throughout Turkey, Africa, and the Middle East. It was then that she was given the name Bakhita, which means “fortunate.”

In slavery she was tortured, whipped, scarred and tattooed, and forced to care for children though she herself was still only a child.

When the Suakin region of Sudan, where her captors were living, was besieged by war, Saint Bakhita and her charges were placed under the care of Italian Canossian Sisters in Venice, Italy (because she had recently been “bought” by an Italian diplomat). When it came time to return to Suakin, St. Bakhita refused to leave the convent. Her captors appealed to the Italian courts, but so did the Sisters.

The courts ruled that, since slavery was not a legal thing in Italy, her captors had no rights to her whatsoever. In their eyes she had never been a slave.

It’s nice to hear a legal case where justice prevailed, no?

St. Bakhita, who claimed that the Sisters had exposed her “to the God she had known in her heart since her birth,” entered the process to become a Canossian Sister. She was assigned a place at the convent in Schio, and remained there the rest of her life as the chef, sacristan, and doorkeeper of the convent, putting her in direct contact with the people of her city.

She was remembered for being gentle, kind, and for “having her mind on God, and her heart in Africa.”

She died on February 8th in 1947. Her body lay in repose, and thousands from the city and across the church came to honor her legacy and memory.

Saint Bakhita is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that the church is a place of sanctuary and, in the face of systems that seek to chip away at the dignity of humanity, must speak out forcefully with both our words and our actions.

-historical bits from public access information

-icon written by artist and theologian Jan Norton