I preached this last Sunday at Saint Paul Reformation in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

“We scar our bodies. It happens.

It happened to my childhood friend, as she looked in the mirror and hated her existence and made little cuts on her legs to take away the pain…

We don’t like to think that it does, but it happens.

Or like, when I was at the doctor last year and he’s doing his routine assessment and I hear him go, “Uhoh…” an utterance you never want to hear, right?

“Better get this checked out,” he said as he thumbed a mark on my side.

Consultations and surgeries later, and now I have a scar from where cancer used to be. I showed the scar to a friend and he thumbed it, asking, “How deep did they cut?”

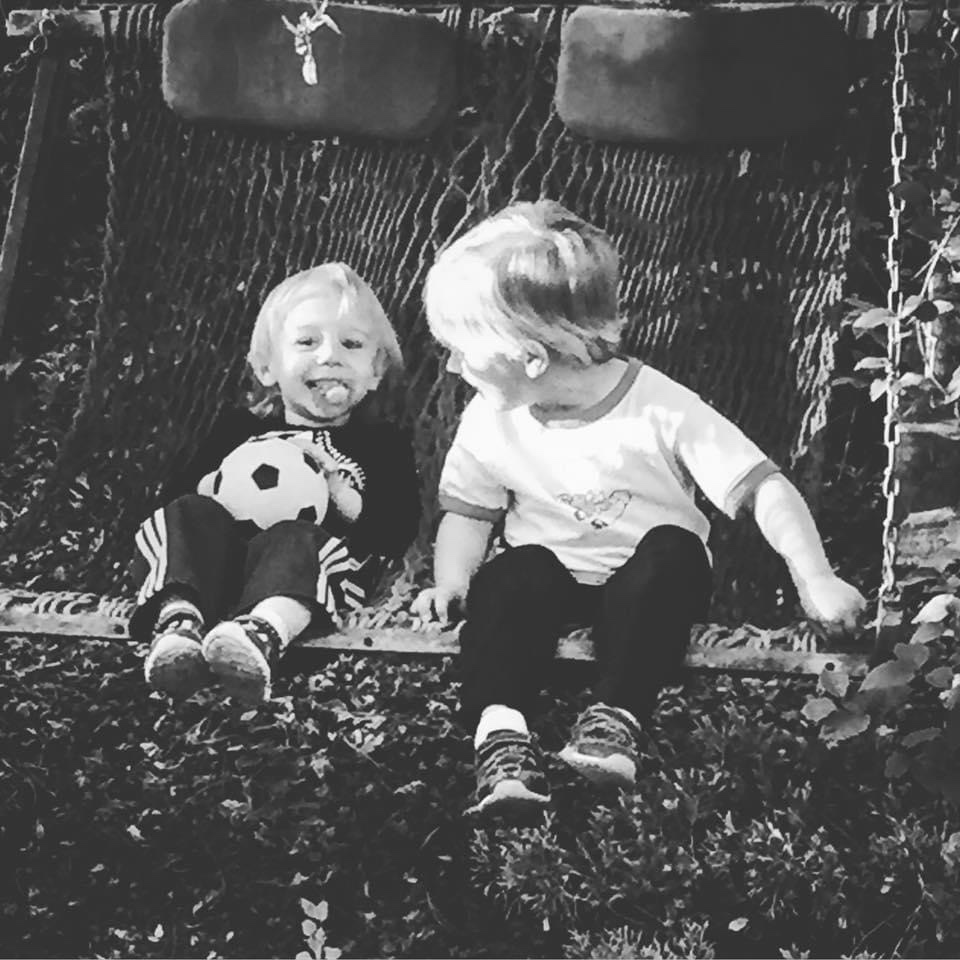

They hadn’t cut very deep, of course. But I was only 40 with two small kids and so though the surgery wasn’t deep or long and didn’t require more than a few hours, the scare of it all was a lot.

“It cut to my core,” I said.

Cancer scars. It happens.

Scars are all around us. Some are even known by their scars. If you wonder if that’s true, ask Harry Potter. Ask Captain Hook. For heaven’s sake the villain in The Lion King is literally named Scar!

Scars happen in this life. It happens.

Minneapolis, your neighbor next door, is scarred from events recent and long ago, events on the street and in the hearts of humans and on the knees on the necks of humans and though I’m aware that the fence between here and there is long and tall, let’s not pretend that Saint Paul doesn’t also bear scars.

All cities. All towns. Scars happen. It happens.

Our court system is scarred and inflicts scars on those unjustly convicted.

Our political system is scarred. Or perhaps that’s a gaping wound.

The church is scarred in more places than we can count, and no amount of long robes can cover it, Beloved, it’s just true, and as a branch manager of the church I have to be honest about that fact…

The disciples in today’s Gospel reading are reeling from scars. Scars upon their reputations, as they look like fools for following that fool, that 165lb Jewish guy who ended up hanging on a cross like every other criminal scarred by an oppressive system. Scars upon their hearts as they mourn their friend. Scars upon their sensibilities as they’ve heard he might be alive, but don’t know what to think about it.

And into that scene enters Jesus, the crucified and risen one, not hiding his scars but bearing them. Bearing them because, well Beloved, God stands in solidarity with those of us scarred by as Saint Prince, a patron saint of these parts, said, “This thing called life.””

Here is the sermon if you’re interested: https://endlessfalling.wordpress.com/2023/04/17/it-happens/(opens in a new tab)