In these November days, an “in-between-time” of the year wrestling with whether it is “fall” or “winter”, we honor perhaps my most favorite theologian and saint who embodied wrestling in his questioning of the struggles of human existence, St. Soren Kierkegaard, Writer, Theologian, and the Father of Existentialism..

Soren was born in Copenhagen in the early 19th Century, the seventh child of aged parents. His father, Michael, was a farm laborer who was born in abject poverty but, through toil and a good bit of luck, succeeded at business and became quite wealthy. There is a story that Michael, deeply unhappy with his life, stood on a hill and cursed God one day…which changed his business fortunes but, in his estimation, also gave him terrible heartache. He believed that God blessed him in business but cursed him in life. His wife and five of his seven children died quite early, and Soren only knew his father as a grieved and sad person.

Soren studied theology and quickly got the sense that God, in retribution for his father’s curse, had summarily cursed the whole family. He tried to cut ties with his father, and lived a quite wild life for a bit, but eventually had a religious conversion that sent him back to make amends. His father died in 1838 and left Soren a considerable fortune.

Kierkegaard eventually finished his theological degree (he was a brilliant student), but never sought ordination because, despite all his study, he could never fully make “the leap of faith,” a phrase he would come to coin and use throughout his work.

In 1849 Soren became engaged to the young love of his life, Regine, but following in the footsteps of his ever-grieved father, was troubled and broke off the engagement when he struggled making sense of inviting someone to share his unhappy existence, this “curse” he felt was still very present.

Breaking off his engagement sent Soren further into a deep and shadowed depression where he publicly (in writing) wrestled with how we know anything at all with certainty.

He began publishing thoughtful works in earnest, using a nom de plume: Either-Or, Fear and Trembling, The Concept of Dread, and many others. The public assumed these were works of fanciful, thoughtful, fiction, but in fact they were Kierkegaard wrestling with life.

As a writer, Kierkegaard became open to public scrutiny, and was engaged in more than a few public feuds with other publications who viewed his work as ridiculous or the mad thoughts of a rich kid who had too much time on his hands. Soren did not take to being mocked, and argued bitterly against his detractors…and all this sent him further into a pit of despair.

His final issue, though, came when Kierkegaard heard officials from the Danish church spout what he identified as sterile theology. Never being able to quite embrace an orthodox faith, Kierkegaard still knew a theology of smoke and mirrors when he saw one, and became quite critical of a church that he felt didn’t take anything seriously and looked to keep people quiet and tamed more than encourage them to adopt deep, thoughtful wrestling.

Soren, in his despair and distress, one day collapsed in the streets of Copenhagen at the age of 42. Doctors diagnosed him with some sort of bone disease, and a month after his collapse he died in November of 1855.

St. Kierkegaard’s big hang-up with the church, and with life, is the notion of how one could talk with such plain certainty about things that are so unexplainable. The inability or unwillingness of the church to faithfully wrestle with itself and its teachings, even core teachings of Divine existence and what constitutes morality in a world that seemed destined for rule by the privileged, troubled him. How does will, risk, and choice play into our life-trajectory? How can a theology that smacked of status quo even begin to mirror the sacrificial life of the Christ?

Kierkegaard always tried to point the church back to this “troubled truth”: you can’t be certain, so stop pretending you can be.

For Kierkegaard truth was experienced more than taught by scholars in a classroom, and in this way he embodied a very “ground-up” theological stance which, for obvious reasons, chaffed against the hierarchy of the Church.

I deeply resonate with St. Soren’s wrestling with faith and truth, and to say that his works Stages on Life’s Way and Fear and Trembling had an effect on me is to say too little. I continue to consider myself a follower of his particular vein of theological inquiry: questioning, uncertain, and yet always striving.

I also think he is an outstanding writer and that you should read him for that, if for nothing else.

St. Soren is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that the people in our pews can be trusted with a bit of ambiguity, can be invited to a deep (and necessary!) wrestling with the faith, and should not be served the vapid theology and trite moralisms and “pie in the sky” escapism.

Wrestle, by God. It’s uncomfortable, it can even be painful, but it is worth the effort to live an examined life.

-the life of Kierkegaard cobbled together from my own work and Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations.

-opinions my own

-do yourself a favor and read Fear and Trembling

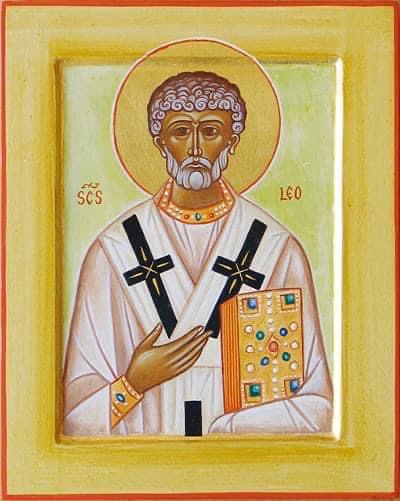

-painting by Fabrizio Cassetta