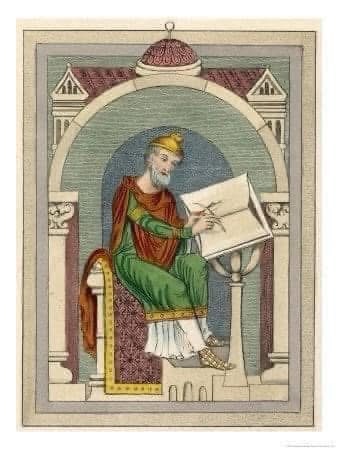

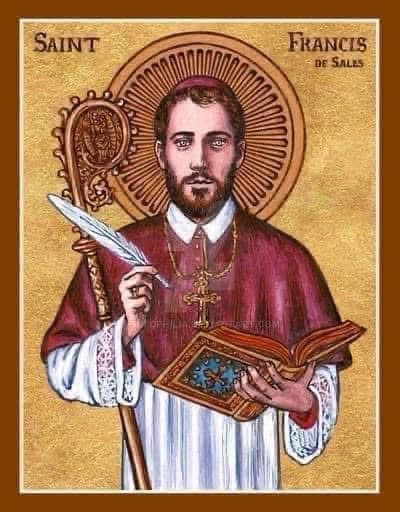

Today the church remembers a 17th Century Saint who was as stubborn as he was prolific: St. Francis de Sales, Bishop of Geneva and Thwarter of Assassins.

Born in Chateau de Sales and educated in the grand cities of France, this St. Francis was ordained a priest (despite his father’s displeasure with the profession), and served for twenty-nine years amidst the uneasy marriage of the Catholics and Calvinists in the Chablais countryside.

He was known around the area for great love for all the people in the land, regardless of their faith. Unfortunately, many others did not regard him with such love, and he had to contend with a few assassination attempts by those who took issue with his Catholicity.

His effective love and preaching did turn many hearts on to the Roman Catholic expression of the church, much to the chagrin of the Calvinists who had worked hard to evangelize in the area.

In 1602 he was appointed Bishop of Geneva, and through this same outlook of love began to slowly change and restructure the diocese, known for being quite difficult and unruly. He gave away almost all of his private money, and lived a simple life. The King of France tried to persuade him to move to Paris, but he opted to skip the pomp of the huge city and remain where he was.

Children are said to have adored him. He took great pains to teach the laity of the church about the faith, something often overlooked by other clergy who preferred to focus on their own scholarly pursuits.

He wrote a number of books, including his twenty-six volume tome, The Love of God.

With Jane de Chantal he founded the Order of the Visitation in 1610 which worked to instruct young women in the faith.

He was stubborn in his love for all people, stubborn in his refusal to live the “high life,” stubborn in his ability to keep living despite the attacks on his life, and stubborn in his belief that God is best known through the eyes of the heart rather than the cold eyes of the head.

Unfortunately St. Frances de Sales died of a stroke at the age of fifty-five. After his death a local Calvinist minister remarked, “If we honored any man as a saint, I know no one since the days of the apostles more worthy than Bishop Frances.”

That kind of love, the love that shines bright enough to cut through animosity and political tension, is rare…and much needed in this world.

St. Frances de Sales is a reminder for me, and can be for the whole Church, that doctrine without love is little more than trite moralism and vacuous philosophical games on parade. Perhaps St. Paul and St. John (and St. George and St. Ringo) were correct: All you need is love.

St. Frances de Sales might have agreed.

-history helped along by Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-Icon written by Theophilia