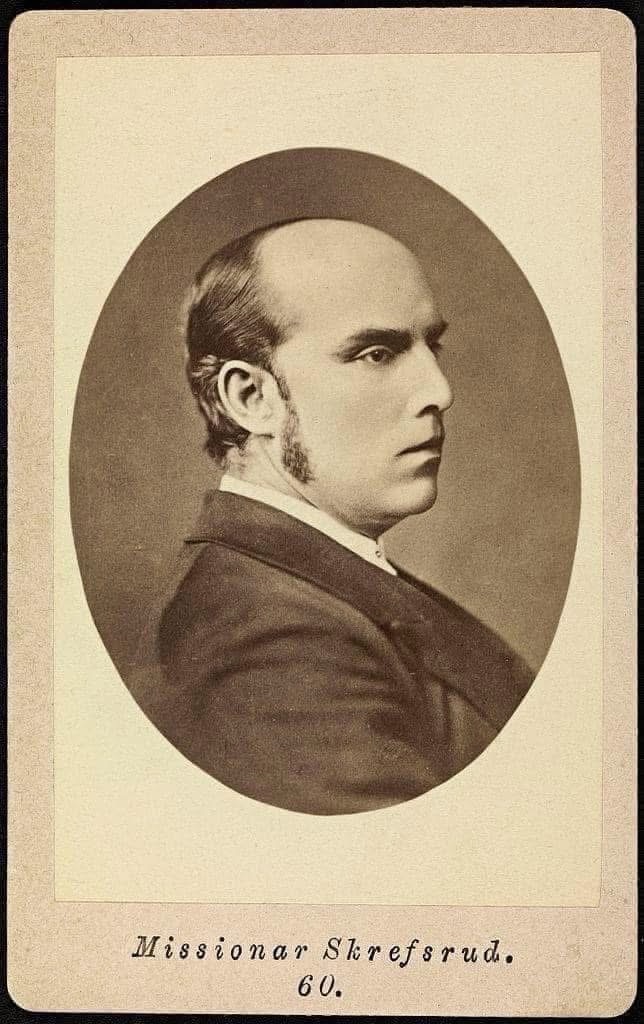

Today the church remembers a more contemporary saint of fascinating and enduring legacy (though you’ve probably never heard of him): Saint Lars Olsen Skrefsrud, Apostle of the Santals and Patron Saint of Second Chances.

Born in mid-19th Century Norway, Lars grew up in poverty and was not really ever formally educated. He studied largely at his local parish and, after being Confirmed, took on an apprenticeship to be a coppersmith.

But St. Lars had more ambition.

He couldn’t afford to pay for an education, and though he took to writing poetry, all of his poems were rejected for publication. He then set his sights on becoming a drummer in the military, but his contemporaries made fun of this idea. All of this compounded together drove Lars to take comfort in the bottle and, after drinking and coercion from those around him, he robbed a bank.

Once arrested, Lars refused to name any accomplices and was sent to prison at the age of nineteen.

In jail, Lars took up the scholarship he was denied in the outside world. He became a model prisoner, and was sent to the sick ward to tend to the ill. Though rejected by his family and friends, one young woman, Anna Onsum, visited him in prison.

Once released (and absolutely without one cent), St. Lars worked as a traveling laborer and made his way to Berlin to the front steps of the Gossner Missionary Society. There he explained his history and his desire to be a missionary. He adopted a monastic way of life and devoted himself to his studies.

In the fall of 1863, St. Lars headed for India. He worked to pay for his passage, and even slept on the deck of the ship. On board he worked alongside people from all over the world, and began to learn the languages of his companions. In 1864 he arrived in Calcutta and was joined by two fellow missionaries and Anna (and they soon married).

Without any aid from any church, the four took up the cause of the Santals, an oppressed tribe in northern India. St. Lars worked day and night to learn the Santali language and adopt their customs and way of living. They built a mission station there, “Ebenezer,” and while they went about their work St. Lars also went about creating a grammar book and dictionary in the Santali language, as well as textbooks, hymnals, and even a translation of Luther’s Catechism.

Most importantly, St. Lars and his companions defended the Santals physically and vocally against their oppressors, and lobbied the British government on their behalf. He aimed to assist them in raising their standard of living.

He said that his ultimate aim was an indigenous Santal church, noting, “We came to the Santals to bring Christianity, not take away their nationality.” In this he was an early adopter of the accompaniment method, rudimentary as it was, of mission work.

In 1873, after the death of his dear Anna, St. Lars took a return visit back to Europe and arrived to much acclaim. The Church of Norway at last ordained him.

At the age of sixty-nine, St. Lars had a massive stroke, but retained the use of his left hand. He continued to write and translate with his left hand until 1910 when he finally died. He was buried in the cemetery at Ebenezer.

The Santal Church continues on to this day, flourishing as a member of the Federation of Evangelical Lutheran Churches in India.

St. Lars is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that accompaniment is the best model for cross-cultural engagement and that everyone deserves a second (and third!) chance.