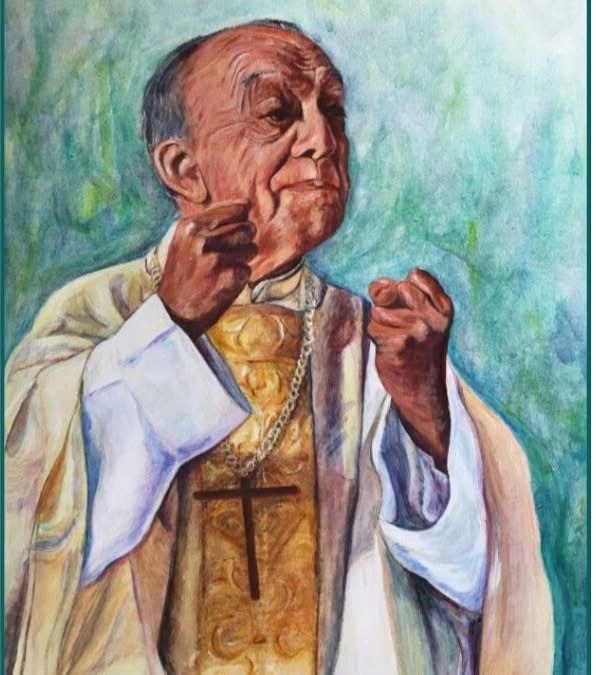

Today the church remembers a 20th Century bishop who scandalized the privileged (and continues to scandalize us today) with just one question : Saint Helder Camara, Archbishop of Recipe, Convert from Far-Right Extremism, and Defender of the Working Class.

Saint Camara was born on this day in 1909 in Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil, a poor northern area of the vast country. He was educated at the local Catholic schools there, and he entered seminary in 1923. Now, for those of you doing the math on that, yeah, he was super young when he entered seminary.

In fact, he was super young when he was ordained a priest in 1931, needing Vatican dispensation because at 24 years old he was below the canonical age.

In his early years as a priest he had been influenced by hard-lined, right-wing politics and theology, backing extremists in local politics. But as he did his work, his heart gradually turned. The politics of oppression and exclusion were hurting the very people showing up in the pews…how could he support politics in one way, and yet serve those being severely impacted by the outcomes of those politics?

I’ll say that louder for those in the back.

In reflecting on this conversion he asked a central question, a question often repeated (and often misattributed to Romero):

“When I fed the poor, they called me a saint. When I asked why they were poor, they called me a communist.”

In 1964 Pope Paul VI appointed him as Bishop of Recife, and was colloquially called “Bishop of the Slums” because he ministered in the streets and encouraged the working poor to seek liberation from the destitute future that the powerful was trying to shove on them.

He entended all gatherings of the Second Vatican Council and, along 40 other bishops, met secretly in the Catacombs of Domitilla to celebrate the Eucharist and sign a pact, encouraging the powerful in the church to live in such a way that they don’t insulate themselves from the poor, but rather stand with them.

Saint Helder was an outspoken critic of the military dictatorship of Brazil in the 60’s, and the Catholic Church there, under his encouragement, began to encourage non-violent resistance, lobbied for land reform, and fought hard for human rights, despite traditionalist Catholic voices of objection who lobbied to have him arrested (or worse) for doing these things.

He practiced a theology of liberation, and even wrote on the topic in the shadow of the Vietnam War is his book, Spiral of Violence.

There are rumors that he advocated for women’s ordination in the church. And while he identified himself as a socialist, he was clear to say that he was not a Marxist nor a communist. “My socialism is special,” he said, “it’s a socialism that respects the human person and goes back to the Gospels. My socialism is justice.”

In his life he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize (without coercion), and in his death he was honored as a Servant of God, the first step toward formal beatification in the Roman Catholic Church.

Saint Camara died on August 27th, 1999, and though we typically honor saints on the day of their death, because the 27th already has a number of saints honored, it’s appropriate today, in the largely barren month of February, to remember this disciple on the day of his birth.

Saint Camara is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church (and everyone?), that when you ask questions that make the powerful squirm, you’re on the right track toward liberation.

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

-historical bits from common sources and Claiborne and Wilson Hartgrove’s, Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals

-icon written by Linda DeGraf