Today the church remembers the reformer and cranky theologian, Martin Luther. He’d wince at being called a saint, but welcomed the title of “baptized.”

Luther was as imperfect as he was ingenious. As the most prolific and public author of his day, his opinions on matters mundane (a homemade remedy for skin rashes) to mighty (Freedom of a Christian) are well-documented and well known by all students of history. He wrote beautiful theological treatises and stirring hymnody. He was a pioneer for women and children in his day.

Yet, he was a person of his era in many ways, and lamentably was unable to rightfully wrestle with his own prejudices, especially toward those of the Jewish faith.

His anti-Semitic writings have been totally and fully condemned by the Lutheran church.

With both his flaws and his fortitude he embodies one of his central theological discoveries: that we are all both sinner and saint, simultaneously. We are both perfectly imperfect, and perfectly loved by a God who has a tender spot for broken things.

One of his more poetic thoughts about the “now-and-not-yetness” of our human existence:

“This life therefore is not righteousness, but growth in righteousness,

not health, but healing,

not being but becoming,

not rest but exercise.

We are not yet what we shall be, but we are growing toward it,

the process is not yet finished,

but it is going on,

this is not the end, but it is the road.“

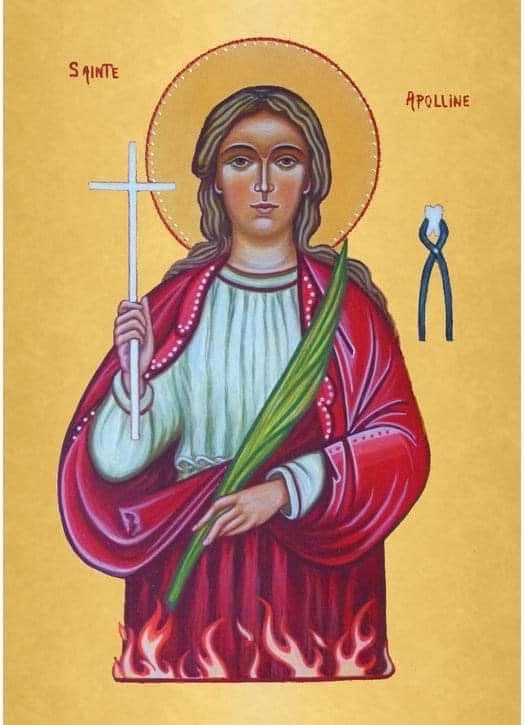

-icon written by Harrison A Prozenko