Good Friday thought:

From the cross, the Christ yells, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In this he was quoting the Psalms, his childhood prayer book.

At the end he was doing what he was taught to do as a boy: say his prayers.

Good Friday thought:

From the cross, the Christ yells, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In this he was quoting the Psalms, his childhood prayer book.

At the end he was doing what he was taught to do as a boy: say his prayers.

As we enter Holy Week, a thought on the events to come:

The Triduum, or Great Three Days, is the antidote to an overly saccharine Easter.

Maundy Thursday gathers the disciples, including you, around a shared table where we all get our feet washed and we all share in dipping our bread in the same bowl as Jesus.

Then the sanctuary is stripped, like our souls now feel stripped, as we realize not only what is about to happen, but also that we must stay to bear witness.

On Good Friday we come not to church, but, with everything bare and the lights low, to a darkened tomb. There we encounter the story of that fateful night, a story we know well not only because we’ve heard it every year, but also because we’ve lived it. It’s familiar.

We’ve all been betrayed by our friends, and have all betrayed a friend. We’ve all been falsely accused and accused others without evidence, let alone our unspoken shame knowing our justice system does this, and profits from it all the time.

We’ve all seen power prey on the powerless. This is that story, but instead of the local courtroom it’s the courtroom of the cosmos.

The reproaches are sung where we’re challenged to answer unanswerable questions of eternal proportions, and the service ends with the cross alone left in the room.

We are, in the end, left only with the cross: this twisted tool of torture to which we now cling, hoping that something good can yet come from it.

Sound familiar?

And then we spend the whole next day in the quiet of non-answers. And at dusk we stream back to that tomb, create a new fire to keep our souls warm, and tell campfire stories of salvation to console ourselves.

“Remember that time that God created the world?” we ask around the fire. “And remember when God saved those folks from the fiery furnace?” We retell these stories as a way to spark hope that, as in those impossible moments, God might be able to do something new with this impossible moment. We teach these stories to our babies, even as we reteach it to ourselves.

And then before we know it, the tomb has turned into a lush garden, and that tomb that was full of death is suddenly full of life: flowers, water, and yes, living bodies.

Our bodies.

Our bodies who now gather around the body of the risen Christ now seen in bread, wine, water, and the faces around us. And we baptize people who have newly heard all of this. And we sing and dance and party because, yup, resurrection has happened again, by God!

The whole arc has import. Every scene plays a part.

Easter is not a day, it’s a journey

For the Christian Celts, the Monday (and sometimes Tuesday and Wednesday) of Holy Week was dedicated to cleaning the house and the home (with Holy Thursday dedicated for cleaning the chapel).

After months of inside smoke from the hearth dusting everything with soot, and with the spots above and around the well-used candles getting dingy and oily, Spring cleaning served both practical and spiritual purposes. Spring was a time of renewal, and so it made sense to renew the home from the dinge of winter.

But, as importantly, Spring cleaning mirrored the inward housecleaning of the Lenten days. With Easter almost upon them. the last few corners of the soul were tended, swept, and exposed to the light for purification.

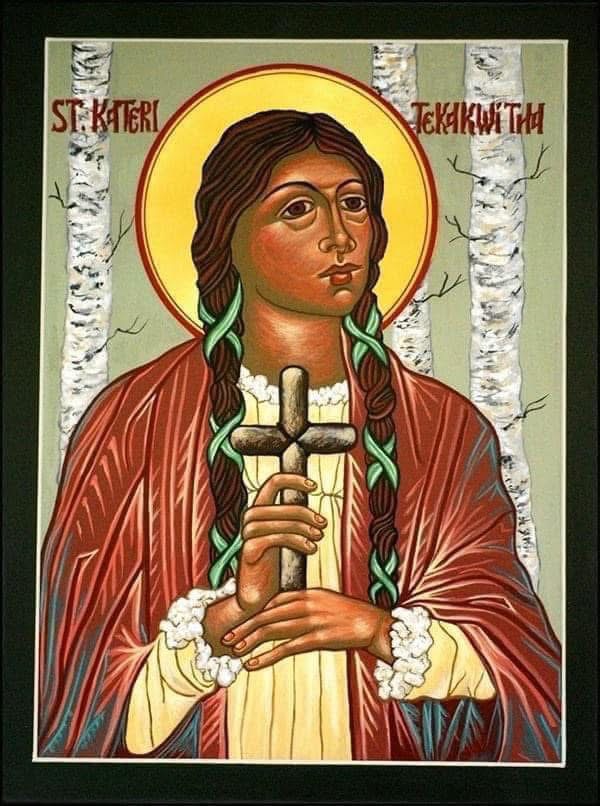

Today the church remembers a 17th Century saint, the first Native American that the church officially canonized: St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the Lily of the Mohawks.

St. Kateri was born to an Algonquin mother who was a practicing Christian and a Mowhak Turtle chief, who was not a Christian. When she was just four years old, a smallpox epidemic took both of her parents and her brother, leaving her with damaged eyesight and noticeable scars on her face. She was taken in by her uncle, who did not approve of her mother’s faith.

At the age of 18, St. Kateri secretly started studying with Jesuit missionaries, and she decided to be baptized and assume the name “Kateri” in honor of St. Catherine of Siena.

A year after her baptism, French conquerors came through and massacred her people and burned their village. St. Kateri escaped by taking to the St. Lawrence River. She was taken in by a First Nations tribe down river who happened to be Christian, and she dedicated her life to prayer and the care for the sick.

At the age of twenty-three St. Kateri contracted tuberculosis, and died shortly before turning twenty-four. Her final words were reportedly, “Jesus–Mary–I love you.”

She was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1980, the first First Nations saint to be canonized (though, truly, many are canonized in the hearts of those who know their stories). She is often referred to as Lily of the Mohawks.

St. Kateri is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that sometimes those who have walked the most unjust roads are the perfect companions for those in need. St. Kateri’s life was ravaged by white invaders who brought their diseases, guns, and unbridled ambition to take over a land and subjugate a people they had no claim to, often in the name of religion and the church.

But, like her Jesus whom she loved so much, St. Kateri was a model for them of true discipleship.

-historical bits gleaned from Claiborne and Wilson-Hartgrove’s Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals

-icon written by Barbara Brocato

Today the church commemorates the Palm Sunday processional in many parishes across the globe. This moveable commemoration is the beginning of the end of the new beginning for Christians who observe the liturgical calendar.

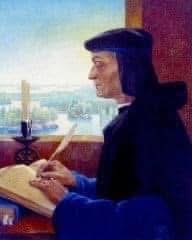

Bishop Theodulph of Orleans penned the hymn my heart is singing on this Palm Sunday morning, “All Glory, Laud, and Honor.”

It truly is one of my favorites, made more sacred by the fact that we really only sing it once a year.

He is said to have written it from his prison tower, thrown there by King Louis the Debonair, son of Charlemagne.

The story goes that the Bishop wrote this hymn and, in the year 821 as the Emperor passed by on Palm Sunday heading to Mass at the cathedral, he sang it loudly over the passing procession from his stone entombment. The emperor, taken with the song, released the good Bishop.

Truly the rocks themselves will shout for justice.

-painting by Polly Castor

Attention my Finnish friends! Attention!

Today the church remembers a Finnish Bishop who studied under Martin Luther himself: St. Mikael Agricola, Bishop of Turku, Renewer of the Church, and Mystic.

Born in Uusimaa (the Fins think “why use one vowel when you can use two?), he went to school in Viipuri and then Turku. He was a good student and due to his scholarly achievements, he was sent by his Bishop to Wittenberg to study under Luther and Malanchthon.

After his graduation, Luther wrote him a letter of recommendation (apparently those have been necessary in the schola forever) and he became Assistant to the Bishop at Turku, eventually succeeding him in the bishopric without seeking Papal approval (a big no-no).

As Bishop St. Mikael undertook extensive Lutheran reforms throughout Finland, encouraging greater participation and catechesis of the laity. Toward this end, he developed an orthography, the basis for modern Finnish spelling, and prepared a book of ABC’s, a prayer book, a New Testament translation, a translation of the Mass, and a collection of Finnish hymns.

Truly, he was an educator as well as a theologian.

After being sent to Russia as part of a delegation to negotiate a peace between Russia and Sweden, he fell ill on the return trip. He died the night of Palm Sunday in 1557 after having been Bishop for only three years.

Though much of his work was in the practical changes needed for an informed church, he was a deeply spiritual person who held ancient mysticism in high regard.

He is widely commemorated in Finland to this day.

St. Mikael is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that you don’t have to be in a position for very long to make a huge difference.

-historical bits gleaned from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

For the ancient Celts, April was the month of new life long before the Christians invaded their lands. They saw the blossoming of the ground and understood deep in their bones that resurrection was not only possible, but probable in this life (and others).

One of the things they took the time to do in these days was connect with trees. They imagined that the trees had their own kingdom, and their own way of communicating (which they do…Google the latest science on the matter!). Tolkien understood this, which is why the Ents played a lovely part in his fantasy world.

Here is the suggestion for deepening your relationship with trees (honestly, they would do this):

-Wander through different groves. Quiet your mind. Touch the trunk of a tree or two and pay attention to it.

-Take a leaf from a tree and rub it between your fingers.

-Sit against a trunk and imagine in gratitude that it gives you shade and fruit (whatever kind it gives) and life.

-Fall into a state of peace and just be with it for a while.

As trees awaken in these April days, the Celts believed humanity, the ground, and the animals would follow that energy and awaken, too.

I think they’re on to something.

It’s worth noting that today the church remembers a contemporary saint who took wrestling with demons, both in his heart and in his country, seriously: St. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Teacher, Martyr, Gadfly of the Nazis.

Born at the turn of the 20th Century in Breslau, St. Dietrich grew up in the intellectual circles of Germany. He studied hard, was trained as a scholar and theologian, and as a young pastor he moved to both Barcelona (where he was assistant pastor at a German-speaking congregation) and then to New York City where he was a visiting lecturer at Union Seminary.

It was during his time in New York that he felt his guts calling him to return home to Europe, the belly of a waking beast, and fight for the soul of his people from the inside. As the Nazi party ascended in 1933, the growing anti-Semitism was alarming to him as a person of faith. From 1933-1935 he served as the pastor of two small German congregations in London, but became the voice of the Confessing Church, the Protestant resistance to the Nazi party’s coopting of the national church. He made his way back to his homeland with both conviction and trepidation.

In 1935 St. Bonhoeffer organized a new underground seminary to train theologians in the art of subversive resistance (because the Divine is subversive!), and he began publishing the thoughts flowing from his heart in this difficult, hidden work. Life Together and The Cost of Discipleship describe the role a Christian is called to play in times of turmoil, and he encouraged his fellow believers to reject the “cheap grace” that smacked of moral laxity.

In 1939 St. Dietrich was introduced to a cadre of political exiles who sought to overthrow Hitler. Working with other church leaders throughout the world, including the Bishop of Chichester, St. Bonhoeffer tried to broker peace deals, but to no avail. Hitler could not be trusted to keep his word, and so the Allies would only accept unconditional surrender.

Bonhoeffer was arrested on April 5th, 1943, shortly after proposing to the love of his life. An attempt on Hitler’s life had failed the previous year, and documents were discovered linking St. Dietrich to the plot.

After a short stay in the Berlin jail, Bonhoeffer was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp, and then on to Schonberg prison. There he wrote letters to his best friend and his fiance, and conducted pastoral duties for the prisoners there.

On Sunday, April 8th, 1945, just after he concluded church services, two men with weapons emerged from the forest, not unlike the soldiers in the Garden of Gethsemane. They said, “Prisoner Bonhoeffer, come with us!”

Bonhoeffer, putting up no fight, said to his fellow prisoner, “This is the end. For me, the beginning of life.”

He was hanged in Flossenburg prison on April 9, 1945.

St. Bonhoeffer wrestled deeply with evil in the world. He was a pacifist theologian, and yet he involved himself in the plot to destroy Hitler because he felt that to not do so would be a greater evil than the man’s death.

St. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church (everyone?!), that wrestling with evil must be something everyone does with honesty and conviction, and that sometimes it comes at a price that can be quite high.

Grace is free, but not cheap.

-historical bits from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-note that sometimes I use the phrase “saint” in the Protestant definition of the word: someone who has died in the faith. Bonhoeffer is not canonized by any official means, just within the hearts of those of us who trust subversion to be the ways of the Divine

-icon written by Kelly Latimore. You can buy his amazing work at https://kellylatimoreicons.com/

Today the church remembers a 16th Century saint who deserves more nods than he typically receives: St. Benedict the African, Friar, Friend of the Blue Collar, and Champion of Humility.

note: St. Benedict shares a feast day with St. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4th but, because it is shared, is usually transposed to the 5th to stand alone

St. Benedict the African was born in 1526 in Messina, Italy as the son of slaves who were converted to Christianity. He was under forced servitude until he was eighteen and, once granted his freedom, made his living as a day laborer. Though he made little money at his work, he shared most of his wages with those who made less than him, and he devoted much of his off time to caring for the sick and infirm.

His race and status in Italy made him the focus of much ridicule and scorn, but his reputation for handling the derision with fortitude and undeserved grace spread. He attracted the attention of Jerome Lanzi, a devotee of St. Francis of Assisi, and St. Benedict was encouraged to join Lanzi’s group of hermits, living a life of piety.

Lanzi died not long afterward, and St. Benedict reluctantly took the helm of the lay order, leading his fellow hermits as they served those who had no one to help them. When Pope Pius IV directed all informal monastic groups to identify with established orders, St. Benedict linked the hermitage with the Franciscans, and he was assigned to serve in the kitchen.

Doing his duties with careful attention and pride, St. Benedict found small ways to enliven the lives of his fellow brothers, and he shunned the lime-light. St. Benedict, throughout his life, wanted to embody the meek way.

In 1578 this brother without formal education (he was unable to read) was appointed as guardian of his Friary. Every account notes that he was the ideal superior: quick witted, theologically profound, gentle, and attuned to the sacredness of life. He often chose to travel in humble ways, at night or with his face covered, not wanting too much attention for his work. He had the scriptures memorized, and he was known for teaching the teachers in many ways.

Toward the end of his life, St. Benedict asked to be removed from his position as guardian of the Friary, and wanted to be reassigned to the kitchen. He died in 1589, and is enshrined still today as a saint worth emulating.

St. Benedict the African is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that education, family, and status are poor indicators of leadership in many ways. Resumes are ego documents that don’t reflect the spiritual sensibilities of an applicant.

-historical bits from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

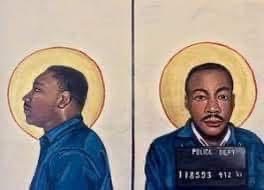

Today the church remembers a martyr and visionary, Saint Martin Luther King, Jr., Dreamer of Dreams and Movement Maker.

Born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1929, Saint Martin was a brilliant young scholar who could have studied anything, literally anything, and chose the ministry as his life’s pursuit. At Crozer Theological Seminary he studied Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, and was greatly moved and impacted by the thought that social change could happen through determination and will, not force.

He received his Ph.D from Boston University in 1955, and started his ministry at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. From there he organized his first social action: a challenge to the racial segregation of public busses, a continuation of the defiance of Rosa Parks and her refusal to give up her seat, and her dignity, to white privilege.

Within a year, due to the organizing efforts of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the busses were desegregated. But not before Saint King’s home was bombed and family was threatened.

In 1960 Saint Martin brought his family to Atlanta where he became co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, sharing the pulpit with his father. In October of that year he was arrested for protesting the segregation of a lunch counter in Atlanta, and in spring of 1963 he was once again arrested in a campaign to end similar segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. The movement withstood dog attacks, fire hoses, police brutality, political sabotage, and a deafening quiet from “respectable religious circles.”

It was from this vantage that he assumed the mantle of the Apostle Paul and wrote from prison what I believe to be his seminal work, Letter from Birmingham Jail, a piece of inspired literature that should be read in communities of faith every year alongside Corinthians, Thessalonians, and Colossians.

Quietism has no place in the church.

On August 28th, 1963 two hundred thousand people marched on Washington in support of The Civil Rights act. It was here that Saint Martin joined Saint Joseph of Egypt and Saint Joseph of Nazareth, all dreamers, telling of his dream that all people will be judged by the content of their character, and not the color of their skin.

In 1964 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace.

King went on to speak out against the war in Vietnam, and took on the case of the poor and the working class in America.

In 1968 he traveled to Tennessee to support striking sanitation workers and, on this day that year, was shot dead by a sniper outside his motel balcony.

Saint Martin’s birthday is honored every year in America, but the church reserves the right to commemorate his feast day alongside the other great martyrs of the church: on the day of his death. We do this not to be morbid or to glorify death, but to rightly honor that often speaking truth to power has consequences.

And yet, speak we must.

Saint Martin Luther King, Jr is a reminder for me, and should be for all people, that non-violent resistance has been so threatening to the powers of the world that they would use violence to snuff it out. And yet the movement continues…you cannot stop a movement based in love and justice.

It lives.

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

-historical bits from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-icon written by Kelly Latimore Icons