Today is World Oceans Day, a day to honor the great incubator of life, the first amniotic fluid of creation: The Seas.

The ancient Celts held the sea in high reverence. Like anything powerful, the sea provided for the people and was also dangerous. It was a road to distant lands as well as a graveyard, a reminder that the wilds of creation are to be respected and not taken for granted.

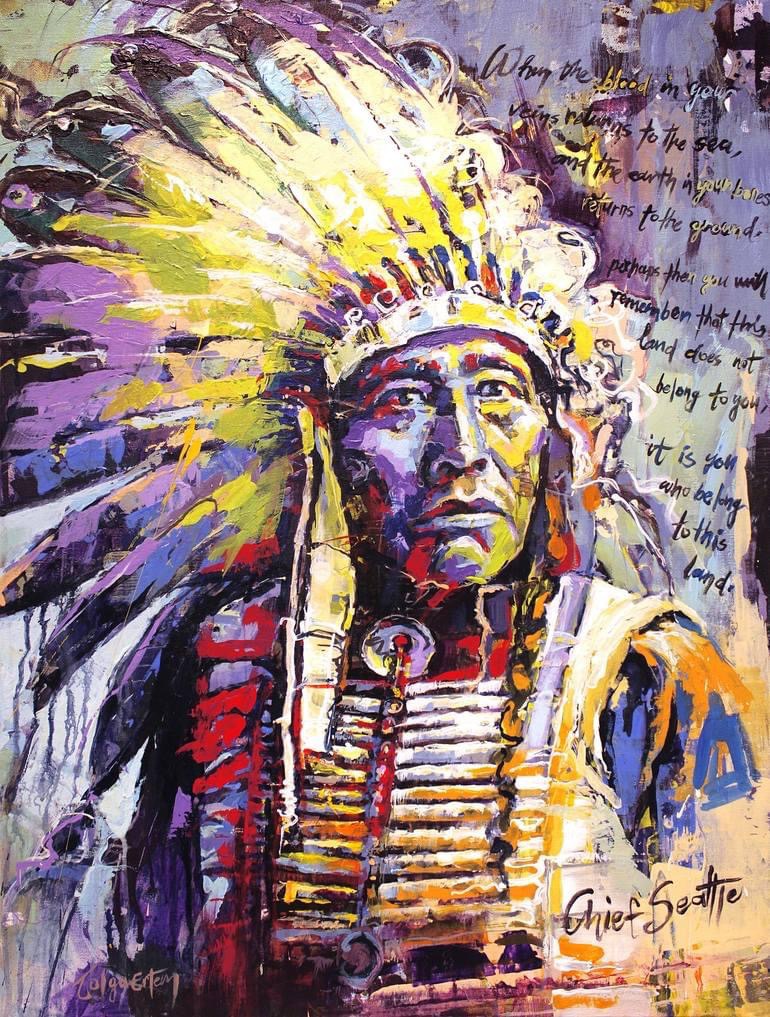

With our modern minds we may imagine that the seas of this world are ours for dominating and using as we please, but with every strengthening hurricane and with every new exploration into the deepest parts of our oceans we are reminded that the oceans still have a temper and a hold a temptation for adventure.

Let us not abuse it nor forget it.

I’ve stood at the base of huge mountains, and I’ve flown over quite a bit of amazing land, and yet it is still the ocean’s siren song that enlivens the most awe in me.

Green and brackish, blue and calm, full of terrors and wonders and teeming with living things yet undiscovered, the oceans of our round rocket ship spinning in this universe are a reminder for me that, even though we may flex our mortal muscles, stronger forces exist and must be honored and respected.

If you’re one who endears themselves to such rituals, the ancients used to thank the Mer-people in these mid-summer months. Mer-folk were known to protect humans as well as correct humans in their courses and, while I certainly don’t believe in such a thing, I understand how the ancients would.

After-all, with so many mysteries beneath the waves, why wouldn’t someone imagine that there might be a whole undiscovered universe of inhabitants who gazed up at the blue sky like we gaze at the briny blue depths, a reflection of what we know…just a little different, you know?

Regardless of what you believe, I hope we can all agree on one thing: the mother of all life, the Oceans, the Seas, deserves not only our thanks and awe, but also our protection.