Churches around the world are honoring Reformation Sunday this Sabbath, a rare treat in that the Sunday and the actual Festival Day almost align.

It’s important to note that each liturgical denomination has a day that honors a formative experience in the life of their particular vein of Christianity. The Eastern Orthodox church celebrates “The Triumph of Orthodoxy” to usher in Lent. The Roman Catholic Church has the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter (February 22nd), emphasizing the founding of the church on Peter’s shoulders. The Anglican Church honors the day the Book of Common Prayer was published, uniting the communion into one.

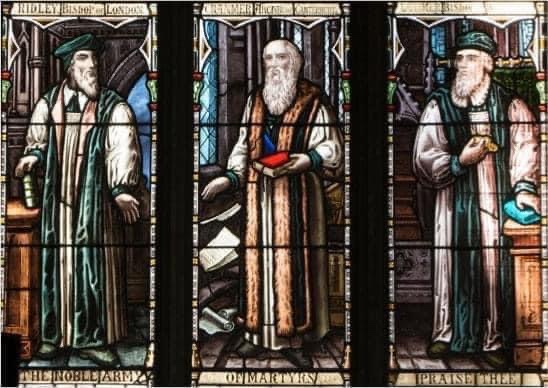

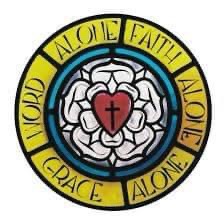

For Lutherans, it is Reformation Day, when we sing “A Mighty Fortress” and “Lord Keep Us Steadfast in Your Word” and dress in red, the color of both the martyrs and the fire of the Holy Spirit.

At its worst the Reformation is celebrated as a triumph. At its best it is a feast day that is simply a continuation of the perpetual change and shift that must happen in a church that is wedded to a God who is known and revealed inside of time.

Historically it does mark a time in history when a break, for better and for worse, happened in the church. This break deserves an autopsy every year in an effort to remember, reaffirm, and repair as much as a possible the schisms that arose from it.

The date of the Reformation, the 31st of October, comes from the lore that Luther nailed his 95 Theses on the Castle Church door in Wittenberg, intending for it to be widely read by everyone who attended the All Saints Sunday mass the following day. We’re not sure this is historically accurate, but because it is so much a part of the narrative around the events of autumn in 1517, we give a nod to its church-changing truth, if not its actual veracity.

A better date to honor the Reformation might actually be June 25th, the date that the Augsburg Confession was presented. Like the Anglican Church with the Book of Common Prayer, the Confession is the binding document of all the reformation churches.

Regardless, tradition compels us to keep the date, to wear red, to remember, and to continue to reform.

-historical bits from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-opinions mine