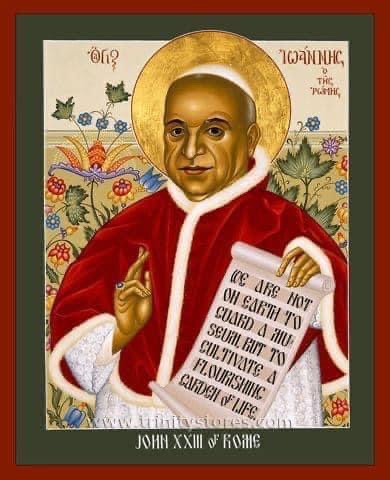

On this day the church remembers Saint Angelo Roncalli, better known as Pope John XXIII.

Born in 1881 to a family of thirteen children in rural northern Italy, Roncalli entered the seminary at the age of 12 and was heavily influenced by the progressive leaders of the Italian social movement.

He was finally ordained in 1904 and served in World War I in the medical and chaplaincy corps while serving in the bishop’s office at Bergamo. During his time in the bishop’s office, he learned social action and gained experience serving the working class.

In 1921 he was called to Rome to serve as the director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. He was consecrated archbishop in 1925 and made apostolic representative to Bulgaria, and then Turkey and Greece in subsequent years.

During his time in the East he built bridges toward Orthodox Christianity, and when World War II broke out, Roncalli was instrumental in passing secretive and sensitive information back to Rome to help Jews fleeing the Nazi regime.

In 1958, at the age of 77, he was elected pope and chose the name John. Everyone expected him to be a buffer between Pope Pius XII and whomever came next, holding down the fort in his old age.

But Pope John XXIII wasn’t having any of that. Building off of his early days working with the poor and his service in the military, he orchestrated an ecclesial overhaul on a massive scale, diversifying the college of cardinals, revising the code of canon law, and calling the Second Vatican Council to shake up the church.

Pope John XXIII’s ultimate goal, it appears, was the re-unification of the church, and (arguably) more than any Bishop of Rome before or since, visited hospitals, prisons, and schools regularly. He was known for, as the folk band Spanky and Our Gang would say, “Giving a damn.”

Today Pope John XXIII is a reminder to me, and to the church, that we can never discount the present moment, regardless of appearances, as being ripe and ready for change.

In many ways he didn’t bother building off of the past, but let some unhelpful and useless ways of operating die on the vine, planting in new soil for a new and changing world. Not everything can be redeemed, Beloved. Sometimes you must start fresh.

And the things that can be redeemed?

Sometimes they need more than refurbishment…they need a huge overhaul.

Huge.

-historical portions gleaned from Pfatteicher’s “New Book of Festivals and Commemorations”