Calling all my Swedish friends! Today’s saint day is for you!

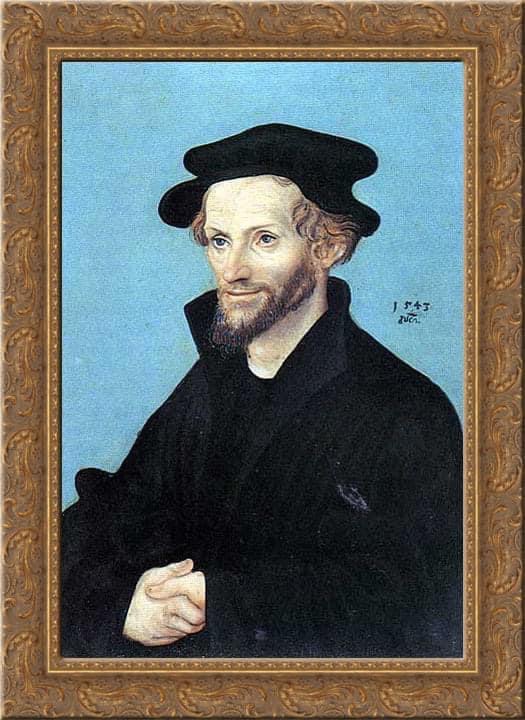

Today the church remembers a 19th Century saint who put pen to paper and out came some wonderful hymns and brooding poems: Saint Johan Olaf Wallin, Hymnwriter, Archbishop, and Restless Existential Wrestler.

Saint Johan was born in Stora Tuna in the late 1700’s and, despite being a sickly child, graduated from the University of Uppsala in 1799. He would go on to receive his doctorate of theology ten years later, and began serving as a parish priest in Solna.

Being a bright and capable pastor, he quickly became a bishop, a chief royal preacher of the King of Sweden, and then shortly before his death was consecrated Archbishop of Uppsala and Primate of the Church of Sweden.

Though he was a great pastor, he was an even better hymnwriter and poet. In 1805 and 1809 he was awarded the highest award for his poetry by the Swedish Academy, and during his life he composed and published a number of hymnbooks containing older hymns he adapted and new hymns he wrote. He was entrusted in editing the new Swedish hymnbook to replace the old one (which had been around since 1695…and people think we hang on to old texts!), and basically did the collecting, editing, and revising the whole thing because the committee assembled couldn’t agree on any drafts (sounds like church work).

King Karl XIV authorized the new Psalmbook (it’s name) in 1819. It included five hundred hymns, a fifth of which were written by Wallin himself.

The Church of Sweden used this hymnbook for over a century. In the next edition (1937) a third of the hymns were still written by Wallin.

On the personal side, Wallin was known as a brooding and rather “stormy-clouded” individual. He wrestled with life, and published an epic poem of restlessness, “The Angel of Death,” written during the cholera epidemic in Stockholm in 1834. He completed the poem just a few weeks before he died on June 30th, 1839 at the age of 60.

You’ve no doubt sung some of his words, and in the Lutheran Church in America’s hymnbook (SBH) his Christmas hymn “All Hail to Thee, O Blessed Morn” was put to Philip Nicolai’s (see October 26th for his saint day) well-sung tune, “Wie Schon Leuchtet.”

Saint Johan is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that beautiful, wonderful, thoughtful people wrestle with life and death.

Indeed, without such wrestling we’d never have real poetry or music that speaks to the soul. Indeed, as Saint Elton of the John’s notes, “Sad songs say so much…”

-historical notes from Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals & Commemorations

-hymn found in SBH #33