Today’s feast day is a great example of how cultures adapt ancient feasts and tweak them to make meaning.

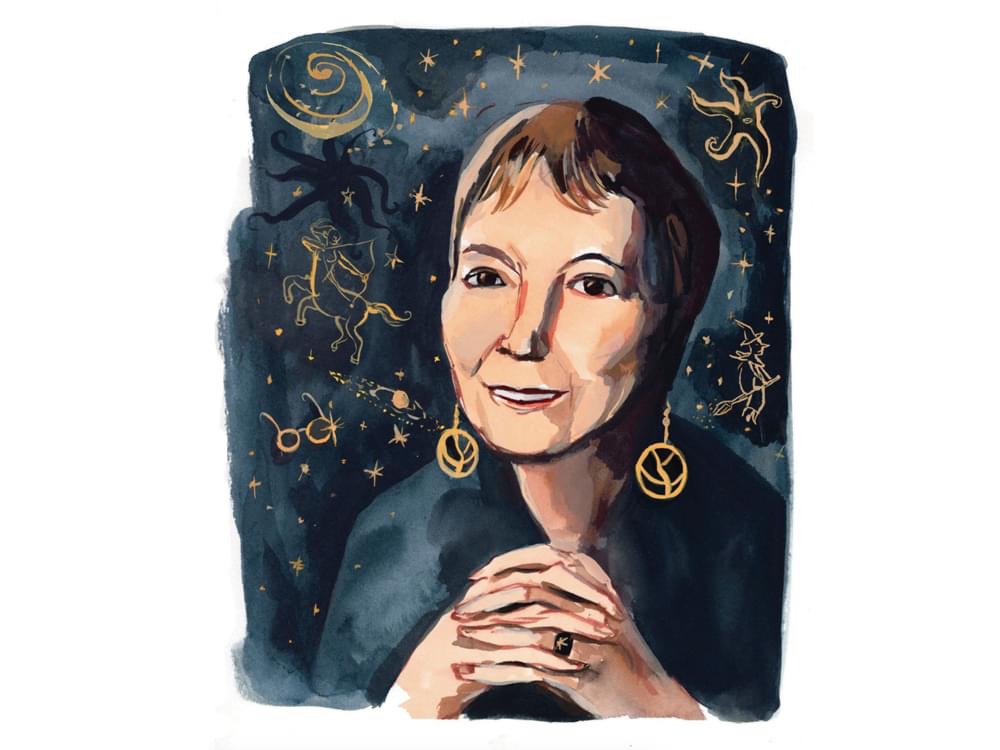

Today the church remembers The Black Madonna of Regla, a feast honored in homes around the world, but which is especially important for our Cuban sisters and brothers (though similar feasts are held in Spain and the Philippines).

The Black Madonna of Regla is an extension of tomorrow’s feast day, the Nativity of Saint Mary, but honors a particular carving of the Madonna from North Africa out of dark wood. The carving was supposedly commissioned by Saint Augustine himself!

When Spain pillaged North Africa (modern day Algeria), they took the statue and placed it in Chipiona, Spain. When the Moors went on their own conquest in Spain, the statue was hidden in a well, and forgotten about for hundreds of years, only to reappear after a vision was given to the church describing its location.

When Spain came brandishing their swords to the Caribbean, they found an ancient feast at this time of year to the goddess of the sea and “mother to us all,” Yemaya. Venerated in Santeria, a blend of many ancient religions, Yemaya is the black goddess dressed in blue who birthed life through the sea, and thus birthed everything. This goddess draped in blue looked, to those Conquistadors, like the Virgin Mary depicted in this ancient African statue so popular in Spain. Thus the festival for Yemaya was adopted as the Feast of the Black Virgin of Regla, because the Christianized celebration was instituted in Regla, Havanna, Cuba.

As with most holidays/holy days coopted by the church, ancient practices of the old remain blended into the new. The Black Madonna, clad in blue with sequins (mirroring the sparkles of the sea) is paraded through the town. The people give thanks for this “Mother of All” and celebrate life. The water of the ocean, like amniotic fluid, is used to symbolize the divine birthing of all life.

For those of a more Christian bent, the Madonna is honored and the life celebrated on this day is the life made whole in the person of the Christ, “Firstborn of All Creation” (Colossians 1:15).

For those who follow Santeria and the more indigenous religions, the woman dressed in blue is Yemaya, who births all life (especially to those who live on an island).

For some, she is both…and that is perfectly fine by them. Clear-cut distinctions in these kinds of matters are important only to people with too much time on their hands and too much at stake with either claim.

By the way, if you think this is unusual, this coopting of feasts and festivals by the church to tweak a practice, know that most of the highest, holiest days of the church are examples of this very thing. Christmas is a cooption, hence why trees of more pagan practices appear in Christian sanctuaries. Candlemas, in February, is a cooption of the Celtic festival of Imbolc. Easter, even, is in some ways a cooption as the very name is derived from the pagan “Goddess of Spring,” Eostre. This is why bunnies sit alongside empty tombs.

This happens. No need to hide it.

The Black Madonna of Regla is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church, that sometimes the Divine is more prism than photograph, with many facets depending where you look…or whose eyes do the looking.