Today the church remembers a 19th Century saint who deserves to be remembered much more widely than she is: St. Sojourner Truth, Abolitionist, Voting Rights Activist, and Fierce Protector of Humanity.

Born in New York under the name Isabella Bomfree, St. Sojourner was bought and sold four times by people who thought they could own other people. At 15 she was joined with another slave and birthed five children, eventually fleeing slavery with her infant Sophia to take shelter with an abolitionist family. That family bought her freedom for $20, and helped her sue to have her son Peter returned to her after he was illegally sold to a family in Alabama.

St. Sojourner Truth moved to New York City and, joining the Black Church movement there, became a charismatic speaker and preacher, proclaiming in 1843 that the Holy Spirit had called her to be renamed Sojourner Truth. In New York City she joined forces with Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison in decrying the demonic pandemic of slavery that spread across the land. She also began speaking out for women’s suffrage, taking up the mantle with Susan B. Anthony.

In 1851 she went on a national tour in the North, famously delivering her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at a women’s suffrage conference in Akron, Ohio. At six feet tall, St. Sojourner brought the audience to attention by pointing out both her strength and femininity make her extremely powerful in equal measure.

St. Sojourner eventually settled in Battle Creek, Michigan to be near her three daughters and help them raise their families. From her outpost in Michigan she continued to preach, speak, and help fleeing slaves escape to the North by providing safe harbor. As the Civil War began, St. Sojourner encouraged soldiers to join the cause of freedom, and became a gatherer of supplies for black Union troops. Because of her efforts, many black regiments were outfitted in ways that the neglectful Northern Army reserved only for white regiments. After the war she was invited to the White House to meet President Lincoln, and began on a new course in life to help the freed slaves find jobs in a fractured America.

Having spent her life as an advocate for others, St. Truth died in 1883 having used up most of her physical faculties (she was both hard of hearing and legally blind at death), but retaining her mental tenacity.

St. Sojourner Truth is a reminder for me, and should be for the whole church (and all people), that the moral arc bends toward justice, but the Divine calls upon all of us to aid in the bending, by God.

Even if it takes a lifetime.

My favorite quote by St. Sojourner is,

“That man say we can’t have as much rights as a man ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman. Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman. Man had nothing to do with it.”

-historical bits gleaned from entry in the National Women’s History Museum

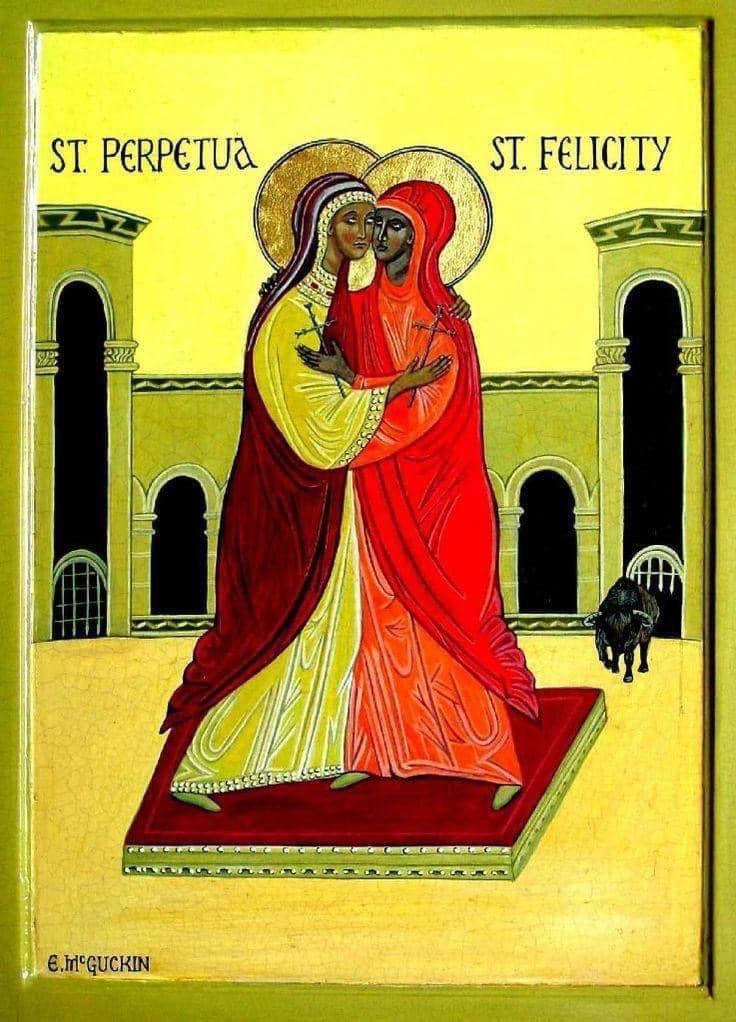

-icon from St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church, San Francisco